July 1, 2019

The 9/11 War Authorization and Iran: An Important Lesson for Congress

Director of National Security Advocacy, Human Rights First

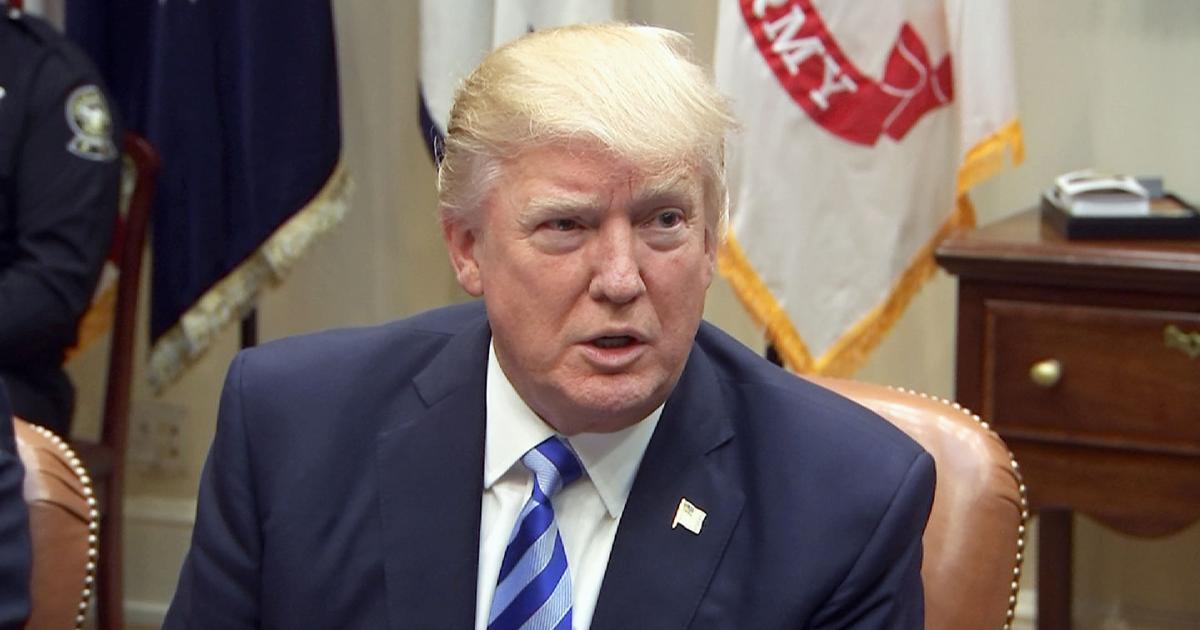

Amid escalating tensions with Iran in June, President Trump told the press that he didn’t need authorization from Congress to go to war with Iran. His bold claim follows on the heels of successive statements by administration officials that the President could rely on the war authorization that Congress passed after 9/11 nearly 18 years later to start a new and unrelated conflict with Iran.

This situation has prompted a round of legal explainers detailing the domestic and international legal issues related to using force against Iran covering the scope of Article II to the restrictions imposed by the U.N. Charter. One of the key legal issues is whether the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF), which authorized force against those responsible for 9/11, provides authority for using force against Iran nearly two decades later, as the administration keeps suggesting. In one legal explainer by former executive branch lawyers, the authors explain why the claim that the 2001 AUMF authorizes force against Iran is “thoroughly unconvincing.” In another, former administration lawyers explain how the Trump administration is wrongly talking as if a mere connection—such as members of al-Qaeda being present in Iran—is sufficient to bring war with Iran within the scope of the 2001 AUMF.

How did we get here?

But if the administration’s claims are as baseless as they seem, then how did we get here? How is the executive branch able to take a war authorization passed by Congress and claim that it provides authority for a new war that is so clearly outside of what Congress intended?

When Congress passed the 2001 AUMF three days after the September 11th terrorist attacks, it intended to provide narrow authority to then-President Bush to use military force against those responsible for the attacks, namely al-Qaeda, as well as against those who had harbored them, namely the Afghan Taliban. Congress rejected the Bush administration’s request for broader, forward-looking authority to use force against unknown future terrorist threats.

But there was also uncertainty in those early days after the attacks about who was responsible and so Congress attempted to preserve some flexibility for the president by not naming precisely who it was authorizing force against, instead providing authority to:

“…use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations or persons.”

Yet despite Congress’s narrow intent, this lack of specificity and other safeguards, such as an expiration date, have led to successive administrations from both parties stretching and expanding the authorization far beyond what Congress originally envisioned. Only Congresswoman Barbara Lee foresaw the risk of the authorization spiraling out of control far beyond Congress’ original intent and voted against it back in 2001.

And just as she feared, the 2001 AUMF has now been invoked as authority for a broad range of military operations in at least 14 countries and against more than half a dozen organizations over the course of nearly two decades. These expansions were based on the legal theory that the 2001 AUMF extended to far flung “associated forces” of al-Qaeda and the Taliban as well as on a theory that the AUMF covered ISIS—a group that did not even exist when Congress authorized the use of force in 2001—because of its al-Qaeda in Iraq lineage.

Calls for the repeal or replacement of the 2001 AUMF

Over the years as the executive branch has stretched the 2001 AUMF far beyond Congress’s original intent, many members of Congress have objected and called for repeal or replacement of the 2001 AUMF. Indeed, earlier this month the House passed for the first time in nearly 18 years an appropriations provision that would repeal the 2001 AUMF eight months after enactment.

But despite these protestations, Congress has been unable to wrest control back from the executive branch. And as a result, the executive branch continues to rely not just on expansive notions of Article II authority to use military force without congressional authorization but to buttress its legal case with the 2001 AUMF.

Perhaps unsurprisingly then, the administration’s suggestions that the 2001 AUMF could be used as authority for war with Iran have provoked a storm in Congress. Members in both the House and Senate and on both sides of the aisle are pushing amendments to the annual defense authorization bills under consideration this month that would restrict the President’s authority to go to war with Iran without Congressional authorization.

While it is a positive sign that Congress is increasingly flexing its war powers muscles, a large part of the reason Congress finds itself in this predicament is because it passed—and left on the books—a war authorization that lacks adequate safeguards against executive branch overreach.

Any new authorization for use of military force should contain safeguards

Congress should learn from its current predicament and not only repeal the 2001 AUMF (as well as the 2002 Iraq AUMF aimed at the Saddam Hussein regime), but also ensure that any new authorizations it passes in the future contain minimum safeguards that prevent the president from using the authorization beyond Congress’s intent. As I argued before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee when testifying on this issue last year, AUMFs that do not include adequate safeguards risk embroiling the nation in new conflicts without public debate or authorization from Congress and make it difficult for Congress to reassert the role assigned to it by the Constitution as the body responsible for declaring war. The current debate around war with Iran is a perfect case in point.

Should Congress decide to authorize the use of military force in the future, it should ensure that any authorization it provides is clear, specific, carefully tailored to the situation at hand, and aligned with U.S. legal obligations under international law. Careful drafting and robust safeguards are critical to prevent any new AUMF from being stretched to justify wars Congress never intended to authorize, to ensure ongoing congressional engagement and an informed public as the conflict proceeds, and to prevent any new AUMF from being used in ways that undermine American values, human rights, national security, or the separation of powers.

To that end, any new use of force authorization considered in the future should contain the following minimum safeguards:

- name the specific enemy

- list the countries where force is authorized

- specify the permitted mission objectives

- require robust reporting both to Congress and the American people

- require compliance with U.S. obligations under international law

- clearly specify that it is the sole source of statutory authority to use force against the enemy named

- set an expiration date

Without these minimal protections, Congress is going to wind up right back in the same predicament it has gotten itself into with the 2001 AUMF.