April 20, 2022

Partners in the Fight for Environmental Justice: Ways That State Attorneys General Can Support Community Efforts

Executive Director, State Energy & Environmental Impact Center at NYU School of Law

Staff Attorney, State Energy & Environmental Impact Center at NYU School of Law

This is the second piece in an eight-month long blog series aimed at highlighting state attorneys general and their work. Upcoming blogs will feature writings from former and current state attorneys general and their staffs.

Environmental justice (EJ) communities (which we define in our Web Resource on Environmental Justice as communities of color and low-income communities that face disproportionate environmental burdens), have been fighting for decades to preserve their right to a healthy environment. Many barriers to that work exist, however. State attorneys general (AGs), as government lawyers, can play an important role in addressing those barriers. Below, we lay out several areas where attorneys general can and, in some cases, have been able to use their unique powers to do just that.

I. THE PARTICIPATION PROBLEM

Where other, wealthier or more politically-connected communities may have access to lawyers to file suit or can apply pressure to policymakers to address pollution and other environmental issues, EJ communities have in some cases historically lacked these resources and thus can face entrenched and structural barriers to remedying environmental hazards.

In 2017, the residents of South Vallejo, California, a community with disproportionately high environmental burdens, learned about a proposed cement factory which would negatively impact the already poor air quality in their neighborhood. In a video about the fight against the plant, advocates describe the resource-intensive movement to resist its approval. Community members spoke with their neighbors to increase awareness, the community needed resources to install air monitoring to characterize the pollution already present, and the attorney general’s office contributed legal expertise by submitting a comment letter describing the compounding negative health effects the plant would have, and critiquing the environmental impact analysis completed for the plant. The fight was a contentious one, but ultimately the community, with the support of the AG, was able to prevent approval of the plant.

This case study highlights both the enormous odds an environmental justice community might face as well as the work that a government attorney, like the state attorney general, can do to support a cause. The principles of environmental justice adopted by the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit emphasize that environmental justice work is community led. This commitment to partnership and community-led decision-making is a key part of movement (or community) lawyering, a concept that was discussed recently in a webinar hosted by the Environmental Law Institute. EJ communities have solutions to the environmental problems they face, and many have goals and desires for the solution process. The role of a lawyer—and specifically of a government lawyer—is to partner in bringing about those solutions.

II. A ROLE FOR STATE ATTORNEYS GENERAL

Attorneys general are the top lawyers in their states, which gives them unique powers and opportunities to make a difference. AGs can and have used their positions to contribute to the work needed to address EJ issues. By supporting citizen science work, promoting strategies to facilitate community engagement, working to ensure that settlement funds from environmental violations return resources to affected communities, and prioritizing communication and empowerment, AGs can help to address the problems raised by participation barriers alongside and in support of EJ communities fighting for environmental justice.

A. Citizen Science

Environmental issues often involve technical scientific questions, and it can be difficult to address those questions as a community member. “Citizen science” aims to bring the community into the discussion by empowering residents to collect data and learn about the science behind the environmental issues they face. In Massachusetts, Attorney General Maura Healey has facilitated community participation through a program focused on air quality. Launched last year, the project monitors air quality in Springfield, MA, which was once called the asthma capital of the United States. Community members provide input on the location of air quality monitors through the Air Monitoring Project Advisory Committee – helping to spread the message regarding air quality in the community, and collaborating with other organizations working for environmental justice in the Springfield region. This participation model empowers community members to take control of the science and documentation of the health hazards they face, provides them with critical data about pollution loads, and empowers them to make stronger arguments for air quality protection (through permit and policy decisions) in and around their community.

B. Stakeholder stipends

Participating in a stakeholder group is a critical way for EJ community members to bring their concerns and proposed solutions before policymakers. However, participation is resource-intensive. Participants may have to commute to the meeting location, may require childcare if the meeting is in the evening, and may need internet access if the meeting is held online. In Washington, Attorney General Bob Ferguson advocated for stipends that community members participating in stakeholder groups can use to address resource barriers. AG Ferguson proposed a bill, which has been adopted as law, which provides stipends for people who participate in stakeholder groups. In addition to reimbursing community members for their expenses, it helps demonstrate that community members’ time and input is valued.

C. Settlements with community benefits

When there is an environmental violation in a community that is already overburdened by pollution, one of the principles of environmental justice is that the community should benefit from any remediation—both through cleanup and direct payments (which might otherwise go into government budgets). Often environmental cases are settled by mutual agreement between the parties before they go to trial, and AGs can work to ensure that those settlements direct funds towards the affected community. For example, in 2011 when the New York AG’s office reached a settlement with the responsible parties over a massive oil spill in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, the settlement included an allocation for a large community fund. The Greenpoint Community Environmental Fund webpage explains that the community collaborates with the AG to distribute the money within the fund and to ensure that projects that receive funds align with local priorities. Community participation allows residents to set priorities regarding what projects are funded and implemented.

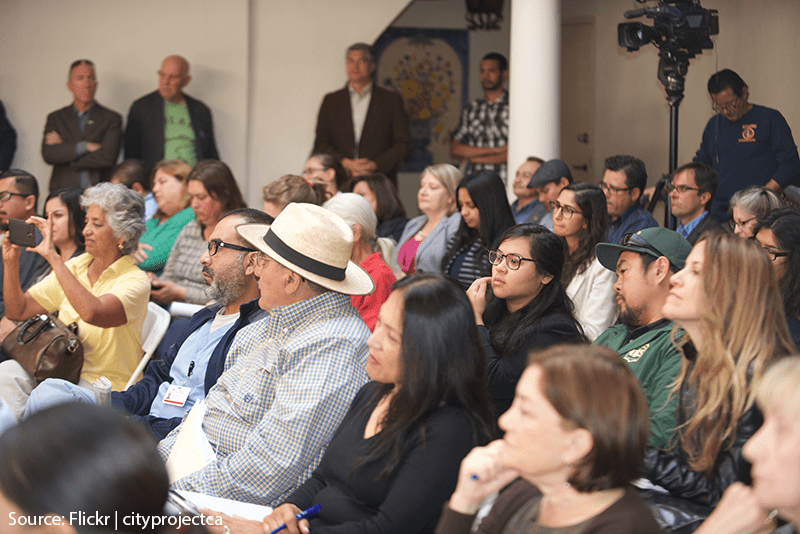

D. Listening sessions

Another participation issue is that community members may feel that their concerns are not heard, or may struggle to use online or phone-based resources to report their concerns to the government. Listening sessions can help to address this issue. In many states, AGs have held listening sessions or town halls, like the session held by the former New Jersey AG on environmental justice programs in the state and the Illinois AG’s recent town hall. The town halls are specifically designed to create a time and place for all interested people, including residents of EJ communities, to speak directly with the AG’s staff members. This helps to remove many barriers that community members might otherwise face when presenting their concerns, priorities, and proposed solutions for environmental problems. For example, residents are not required to go through websites or fill out what might be complex forms reporting violations, residents are not required to have internet access or even phone service when town halls are held (safely) in person, and residents are able to speak face-to-face with government staffers, which helps to build connections and trust.

III. CONCLUSION

AGs can play a critical role in boosting the work of EJ community advocates as they partner with them to achieve the goals of the community. Removing barriers to participation is a critical component of EJ work. These examples show some of the tools AGs have and should use to address those barriers. To learn more about environmental justice and the ways AGs are confronting environmental injustices, please see Expanding AG EJ Practice, produced in partnership between WE ACT for Environmental Justice and the State Energy & Environmental Impact Center.

Bethany Davis Noll is the Executive Director of the State Energy & Environmental Impact Center at the NYU School of Law. She is a member of the ACS State Attorneys General Project’s Council of Advisors. You can find her on Twitter at @bdavisnoll.

Colin Parts is a Staff Attorney at the State Energy & Environmental Impact Center at the NYU School of Law.

Environmental Protection, Environmental Regulation, Roles of State Attorneys General, State Attorneys General