April 27, 2018

I Thought I Was Safe from the Purge. I Was Wrong.

On January 10, 2018, I sat in the gallery of the Supreme Court of the United States listening to oral argument in Husted v. A. Philip Randolph Institute. The question presented was whether the state of Ohio’s practice of updating its voter rolls by purging people who fail to vote in consecutive elections violates the National Voter Registration Act of 1993 and the Help America Vote Act of 2002. As an Ohioan, I was very interested in the case. I was born and raised in Northeast Ohio, attended law school at The Ohio State University, and have voted in every single primary, special, and general election since I turned 18.

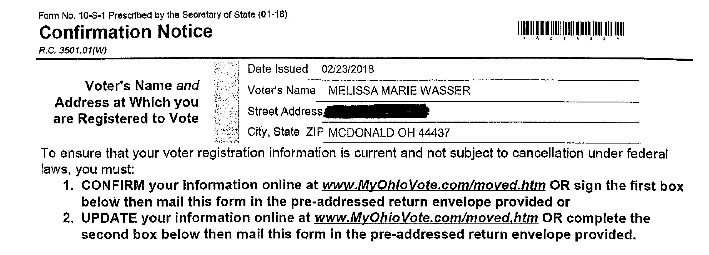

During oral argument, I heard many stories of people being aggressively purged for failing to vote and failing to respond to a confirmation notice. I even saw Oak Harbor’s mayor, Joe Helle, confront Secretary of State Jon Husted outside the Court, demanding to know why he, an Army veteran, had been purged from the rolls upon returning from service overseas. Before this case, I disagreed with Ohio’s process in removing voters from the rolls but believed that voting and staying engaged would safely keep people registered. Imagine my surprise a month later when, despite my continuous voting over the past eight years, the state of Ohio sent me a confirmation notice.

Perhaps I should not have been so surprised. After all, Ohio is the most aggressive state in purging its voter rolls. If an Ohioan does not vote in one federal election cycle, the county board of elections sends the individual a confirmation notice. Failing to respond to this notice and cast a ballot in any election in the next four years results in the removal of a name from the voter roll. Secretary of State Jon Husted argues that the failure to vote suggests a person has moved from their address. He does not seem to understand that a voter may miss one election for other reasons, such as not liking the candidates or not being able to navigate a hectic schedule. Other secretaries of state send out confirmation notices when the state has received some affirmative evidence of a move, such as notice from the United States Postal Service.

In discussing the history of the NVRA during oral argument on January 10th, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg noted that Congress “didn’t want [a] failure to vote to be a trigger” for the confirmation notices. And it should not be. We should seek to fulfill the purpose of the NVRA— to increase the number of eligible citizens who can register to vote and participate in the franchise—not to remove them from the rolls and keep their voice out of our electoral system. Furthermore, what my situation has demonstrated is that Ohio should not use a process that in addition to shrinking the electorate is also faulty. My confirmation notice proves that you can follow the system and vote in every election, and still face a potential purge from the voter rolls.

Secretary Husted often touts his mission as “mak[ing] Ohio a place where it is both easy to vote and hard to cheat” and has said that “by any objective measure we have achieved this goal.” I disagree. By wrongfully disenfranchising thousands of Ohio voters, the right to vote has been severely diminished. In 2016 alone, more than 70 million registered voters across the country did not cast a ballot, and in the three biggest counties in Ohio, 144,000 Ohioanswere unlawfully purged from the rolls.

In 2016, the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit ruled against Secretary Husted and the Ohio voter removal process, finding that the state violated the NVRA by using the failure to vote as a “trigger” for sending voters confirmation notices. The right to vote is a fundamental one and having a “use it or lose it” policy in Ohio is wrong and misguided. This Term, the Court should take a page out of the Husted playbook and make it “easier for people to vote” by ruling that Ohio’s purging process violates the NVRA in Husted v. A. Philip Randolph Institute.