October 12, 2017

Did President Trump Obstruct Justice?

Russia Probe

by Barry H. Berke, co-chair, Litigation Department, Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel LLP; Noah Bookbinder, executive director, Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington; and Norman Eisen, Senior Fellow - Governance Studies, The Brookings Institution

*This piece was originally published by The Brookings Institution.

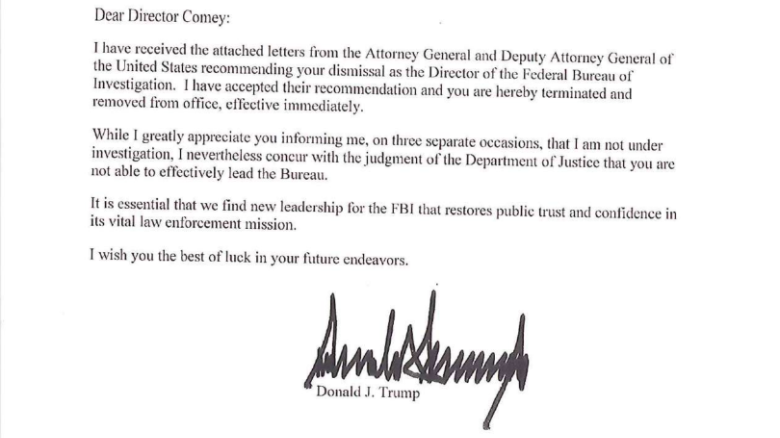

There are significant questions as to whether President Trump obstructed justice since taking office. We do not yet know all the relevant facts, and any final determination must await further investigation, including by Special Counsel Robert Mueller. But as we demonstrate in a new paper, “Presidential obstruction of justice: The case of Donald J. Trump,” the public record contains substantial evidence that President Trump attempted to obstruct the investigations into Michael Flynn and Russia’s interference in the 2016 presidential election through various actions, including the termination of James Comey.

As we explain in our paper, attempts to stop a government investigation represent a common form of obstruction. Demanding the loyalty of an individual involved in an investigation, requesting that individual’s help to end the investigation, and then ultimately firing that person to accomplish that goal are the types of acts that have frequently resulted in obstruction convictions, as we detail in our paper. In addition, to the extent the president’s conduct could be characterized as threatening, intimidating, or corruptly persuading witnesses, that too may provide additional grounds for obstruction charges. There is also an important question as to whether President Trump conspired to obstruct justice with senior members of his administration although the public facts regarding conspiracy are less well-developed.

While those defending the president may claim that expressing a “hope” that an investigation will end is too vague to constitute obstruction, we show that under applicable precedents such language is sufficient to do so. In that regard, it is material that former FBI Director James Comey interpreted the president’s “hope” that he would drop the investigation into Flynn as an instruction to drop the case. That Comey ignored that instruction is beside the point under applicable law. Potentially misleading conduct and possible cover-up attempts could serve as further evidence of obstruction. The president’s actions that might qualify as such evidence include: fabricating an initial justification for firing Comey, directing Donald Trump Jr.’s inaccurate statements about the purpose of his meeting with a Russian lawyer during the president’s campaign, tweeting that Comey “better hope there are no ‘tapes’ of our conversations,” despite having “no idea” whether such tapes existed, and repeatedly denouncing the validity of the investigations.

Arguments that the president has no potential obstruction exposure whatsoever are unpersuasive. The claim that the president’s legal authority to remove an FBI director is an absolute bar to obstruction liability is a red herring. As a matter of law, the fact that the president has the authority to take a particular course of action does not immunize him if he takes that action with the intent of obstructing a proceeding for an improper purpose. The president will certainly argue that he did not have the requisite criminal intent to obstruct justice because he had valid reasons to exercise his authority to direct law enforcement resources or fire the FBI head. While we acknowledge that the precise motivation for President Trump’s actions remains unclear and must be the subject of further fact-finding, there is already evidence that he may have acted with an improper intent to prevent investigations from uncovering damaging information about Trump, his campaign, his family, or his top aides.

Special Counsel Mueller will have several options when his investigation is complete. He could refer the case to Congress, most likely by asking the grand jury and the court supervising it to transmit a report to the House Judiciary Committee. That is how the Watergate Special Prosecutor coordinated with Congress after the grand jury returned an indictment against President Nixon’s co-conspirators. Special Counsel Mueller could also obtain an indictment of President Trump and proceed with a prosecution. While the matter is not free from doubt, it is our view that neither the Constitution nor any other federal law grants a sitting president immunity from prosecution. Regardless of how that question is resolved, there is no doubt that a president can face indictment once he is no longer in office. Reserving prosecution for that time, using a sealed indictment or otherwise, is another option for the special counsel.

Congress also has actions that it can take, including continuing or expanding its own investigations, issuing public reports, and referring matters for criminal or other proceedings to the Department of Justice or other executive branch agencies. In addition, there is the matter of impeachment. In its examination of the articles of impeachment drafted against Presidents Richard Nixon and Bill Clinton, as well as those drafted against Judges Harry Claiborne and Samuel Kent, our paper shows that Congress has previously considered obstruction, conspiracy, and conviction of a federal crime to be valid reasons to remove a duly elected president from office. Nevertheless, the subject of impeachment on obstruction grounds remains premature pending the outcome of the special counsel’s investigation.

Download “Presidential Obstruction of Justice: The Case of Donald J. Trump.”

*Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW) is a party (and is providing representation to other parties) in active litigation involving President Trump and the administration. Noah Bookbinder is the executive director and Norman Eisen is the chair and co-founder of CREW. Barry Berke and Kramer Levin are outside pro bono counsel to CREW.