October 3, 2017

Did President Trump Declare War on North Korea?

Ashley Deeks

by Ashley Deeks, Professor of Law and Senior Fellow, Center for National Security Law, at the University of Virginia School of Law

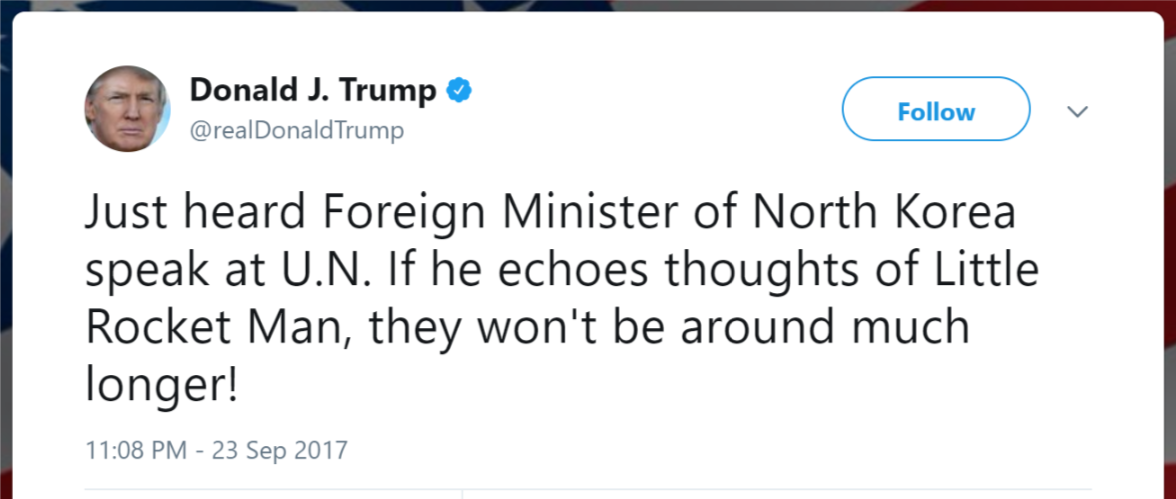

Last week, North Korea’s Foreign Minister claimed that President Trump had “declared a war” on his country. He apparently reached that conclusion based on President Trump’s tweet stating that North Korea “won’t be around much longer” if the Foreign Minister’s U.N. speech accurately represented the thoughts of Kim Jong Un. In response to this alleged U.S. declaration of war, the Foreign Minister threatened that North Korea would shoot down U.S. aircraft flying off the North Korean coast, even if the aircraft were in international airspace.

Is North Korea correct that President Trump declared war? And if so, what follows as a legal matter?

The short answer is that President Trump has not declared (and constitutionally cannot declare) war with North Korea. First, as a matter of international law and international relations, states no longer “declare war” against each other. Today’s international system is regulated by the U.N. Charter, which provides that states must refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force. The only lawful exceptions to this prohibition are actions taken in self-defense or pursuant to authorization by the Security Council. States acting pursuant to one of these two exceptions would have little reason (legally or politically) to declare war, and there are few examples in recent history of states declaring war when acting in self-defense. As a result, declarations of war may now carry a patina of aggression – something no state wants to be seen as undertaking.

Second, as a matter of U.S. domestic law, the Constitution clearly provides that Congress, not the Executive, will “declare war.” Congress last formally declared war against other states in 1942 (against Bulgaria, Hungary, and Rumania). Today, Congress authorizes the president to engage in armed conflict through the use of Authorizations for the Use of Military Force. For instance, Congress authorized the president to use force in 2001 against al Qaeda and the Taliban, and in 2002 it authorized him to invade Iraq. (A full list of declarations of war and authorizations for the use of military force can be found in this Congressional Research Service report.)

Third, as a factual matter, President Trump’s tweet is hardly unambiguous. It seems quite likely that North Korea’s response to it is driven entirely by politics, not by an actual belief that Trump has, as a legal matter, initiated a de jure state of war between the two countries.

The fact that the U.S. system assigns Congress the formal war powers does raise an interesting question, however. International law generally treats states as black boxes, which means that one state is not usually expected to know how other states’ internal decision-making processes work. Thus, it is conceivable that a U.S. president could issue a statement that clearly appears to be a declaration of war, and that another state could fairly rely on that statement to construe itself to be in a formal state of war with the United States, in the belief that U.S. presidents may declare war. That is not the factual situation in play here, however.

Putting together the ideas that (1) states rarely issue declarations of war today and (2) in the U.S. system, Congress declares war, President Trump’s tweet should not be (and cannot reasonably be) construed as constituting a declaration of war. What really matters here are actions, not words. The key question is what, if anything, the president orders the U.S. military to do moving forward. Although Congress is constitutionally assigned the “declare war” power, this does not mean that the Executive cannot undertake military action without prior congressional authorization. There are dozens of examples of situations in which the President has deployed military forces abroad without congressional blessing – including the Korean War, the attempted rescue of Americans in the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, and airstrikes in Libya in 2001, to name just a few. It remains to be seen, of course, what roles the President and Congress choose to play in navigating these tense relations with North Korea. But we are not at war yet.

Constitutional Interpretation, Executive Power, Separation of Powers and Federalism