September 10, 2018

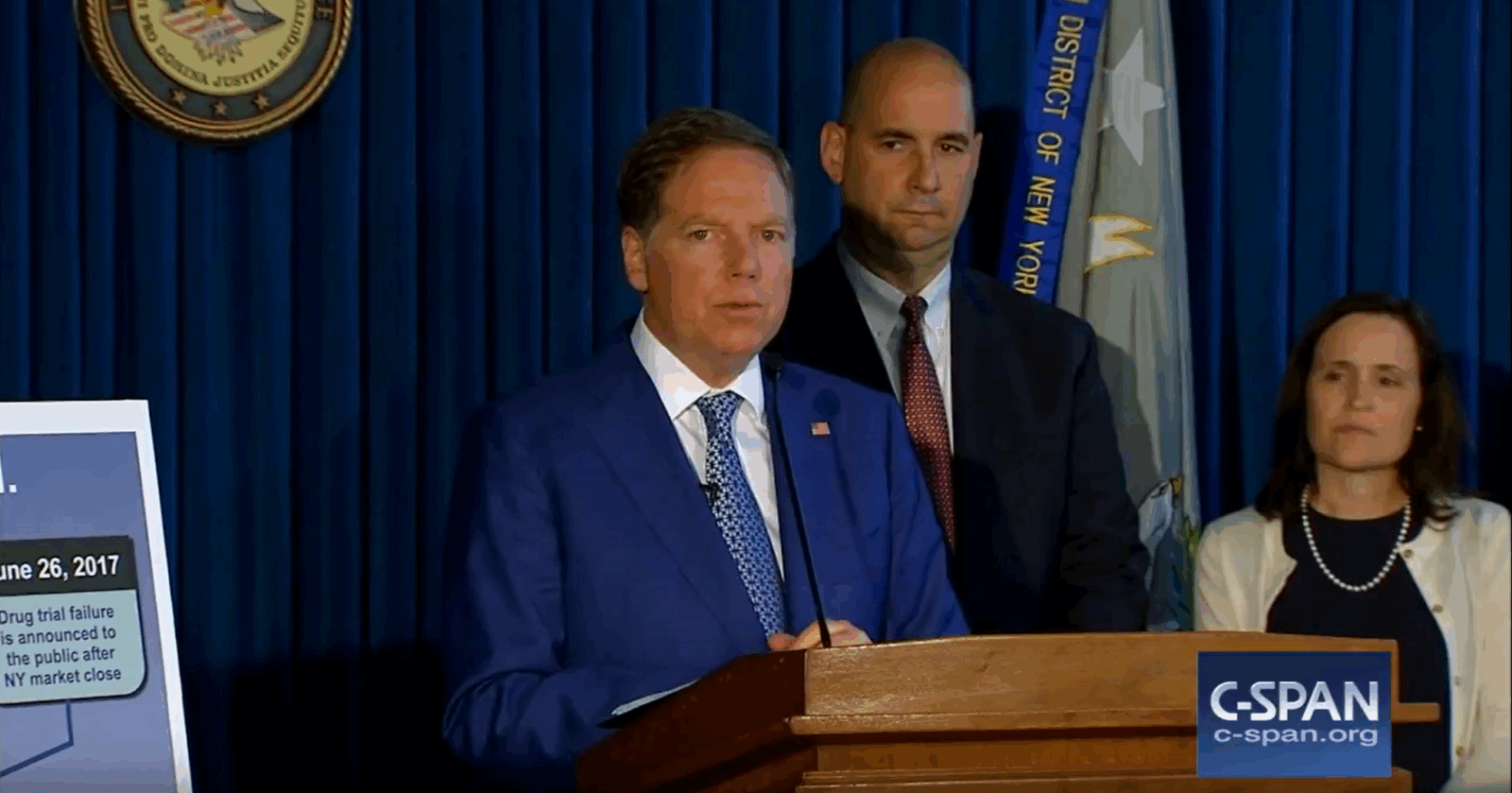

Christopher Collins and Congressional Conflicts of Interest

On August 8, Geoffrey S. Berman, the interim U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, announced the indictment of Representative Christopher Collins (R-NY), his son Cameron Collins, and Stephen Zarsky, father of Cameron Collins’s fiance. The 13-count indictment alleges insider trading and related crimes: one count of conspiracy to commit securities fraud, seven counts of securities fraud, one count of conspiracy to commit wire fraud, one count of wire fraud, and three counts of making false statements to FBI agents - one count of lying for each of the three defendants. The indictment is here.

Media attention to the Collins indictment was brief; it was displaced by, among other events, the Manafort trial and convictions, the Cohen plea, the passing of Senator McCain, and the Kavanaugh confirmation hearings. The significance of the indictment, however, should be undiminished, especially in light of the imminent Congressional midterm elections.

The factual predicate for the crimes alleged in the indictment is uncomplicated. Representative Collins owns shares in Innate Immunotherapeutics Limited, an Australian company that developed a drug called MIS416. According to the indictment (see paragraph 3), Collins served on the board of directors of Innate, was one of its largest shareholders, and “...regularly had access to material, non-public information about MIS416...”

Collins encouraged his son and Stephen Zarsky to buy shares. Other family members and friends also bought shares, including Zarsky’s spouse and daughter, who was Cameron’s fiance. (Several of Collins’s Republican colleagues in the House also bought shares in Innate, but none of them are implicated or even mentioned, passim, in the indictment.)

On June 22, 2017, during the Congressional Picnic at the White House, Representative Collins learned from Innate’s CEO that MIS416 had failed its trials - before Innate publicly disclosed the information. Although he could not sell his shares at that time (more about that below), Representative Collins allegedly called his son immediately and shared this material, non-public information. Also before the information was publicly disclosed, Cameron Collins allegedly passed it on to Stephen Zarsky and three other shareholders. In turn, Zarsky allegedly shared the same material, non-public information with three more persons who’d bought shares in Innate.

Before Innate publicly announced the failure of MIS416, Cameron Collins, Zarsky, and several of the six other tippees sold their shares. The sellers thus avoided, in the government’s estimation, $768,000 in losses they would have incurred “...if they had sold their stock in Innate after the Drug Trial results became public.” The basis for the government’s arithmetic: after Innate publicly disclosed MIS416’s failure, its stock crashed, losing approximately 92% of its value in just one day of trading.

Unlike Cameron Collins, Zarsky, and the tippees who sold their shares, Representative Collins didn’t take advantage of his insider knowledge and trade out of his position in Innate before the stock cratered. The indictment alleges that Representative Collins held his shares in Australia and was, therefore, subject to a trading halt on the Australian Stock Exchange that Innate had requested around the time it privately notified Collins of the results of the drug trial, but before the public announcement of the drug’s failure in trials. During the subsequent criminal investigation, Rep. Collins, Cameron Collins, and Zarsky allegedly lied to FBI agents when interviewed about their conduct.

The securities fraud and wire fraud charges - and associated conspiracy counts - arise, therefore, out of this alleged insider tipping and/or trading by the Congressman, his son, and Mr. Zarsky. The false-statement charges arise from the defendants’ alleged lies to FBI agents about their conduct. To date, none of the other tippees have been indicted.

The FBI and the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York are not the only government entities interested in Rep. Collins’s Innate activities. As the indictment also notes, the Congressman “...was already under investigation by the Office of Congressional Ethics (‘OCE’) in connection with his holdings in, and promotion of, Innate.” Per the indictment, Rep. Collins had been interviewed by OCE personnel about his involvement with Innate 17 days before he was confidentially informed by its CEO about the drug’s failure in trials and allegedly tipped other investors. On July 14, 2017, the OCE referred its investigation of Collins to the House Committee on Ethics.

It’s possible that the House ethics committee’s investigation will be suspended while the criminal prosecution proceeds. Meanwhile, Rep. Collins announced that he is suspending his campaign for re-election to the House.

All of this investigative activity might, on the one hand, end in exoneration of Rep. Collins by the House ethics committee and acquittals on, or dismissals of, the criminal charges against Collins, his son, and/or Zarsky. On the other hand, there could be some combination of pleas and convictions, with censure or expulsion of Collins by the House (though House action will be moot if Collins does not win reelection).

Regardless, there is a threshold issue that deserves substantial attention in this election season: Article I, Section 5, clause 2 of the Constitution provides that "Each House may determine the Rules of its Proceedings, punish its Members for disorderly Behaviour, and, with the Concurrence of two thirds, expel a Member." On this constitutional basis, Congress sets and enforces its ethical requirements for its members.

As noted on his Congressional website, “Congressman Collins serves on the House Energy and Commerce Committee in the 114th Congress. He currently serves on three Subcommittees: the Communications and Technology Subcommittee, Health Subcommittee, and Oversight and Investigations Subcommittee.” (Emphasis added.) The Office of Congressional Ethics referred Collins to the House ethics committee in part for this conduct:

Representative Collins attended a meeting at the National Institutes of Health (“NIH”) in November 2013. In that meeting, Representative Collins discussed Innate and requested that an NIH employee meet with Innate employees to discuss clinical trial designs. If Representative Collins took official actions or requested official actions that would assist a single entity in which he had a significant financial interest, then he may have violated House rules and standards of conduct.

The linchpin of this syntax is that Collins’s conduct “may have violated House rules and standards of conduct.” The standard for Congressional conduct ought to unambiguously prohibit corporate board-membership and active ownership or other financial interests in businesses by members of Congress.

Rules of professional conduct generally regulate and limit how lawyers may acquire or hold financial interests in clients. See, e.g., ABA Model Rule 1.8(a). The rules of judicial conduct likewise contemplate that judges will limit their financial activities vis-a-vis their duties on the bench. See, e.g., Canon 3, Rule 3.11 of the ABA Model Code of Judicial Conduct.

Legislators write and amend laws and investigate the outcomes of their law-making - and they investigate the federal agencies charged with enforcing the laws they enact. Legislators can advantage or disadvantage themselves or other stakeholders through their legislative duties. They should, therefore, be subject to strict ethics requirements.

During the current election cycle, the public should insist that candidates for Congress pledge that, if elected, they will divest themselves of their significant financial interests before taking office. More generally, the public also should insist that Congress institutionally require its members to divest before taking office or, at a minimum, to transfer their significant financial assets to blind trusts. In either event, members also should be required to recuse themselves from participation in any legislative activities where they know or believe - or a reasonable person would know or believe - that their personal financial interests might be affected by their legislative work.

Of course, devising Congressional conflict-of-interest rules that account for all of the variations and complexities in individual legislators’ financial affairs might not be easy or simple. For example, tax laws affect the economics of home-ownership (as underscored by the recent changes to federal income-tax laws). A home is an asset - and perhaps the only substantial asset - that many lower-income legislators might own. That said, divestment to the fullest feasible extent should be the default setting for members of Congress.

Legislators should serve only the public interest and not their personal financial interest. There might be sacrifices or inconveniences involved in public service, but strict - and strictly enforced - legislative conflict-of-interest laws might have multiple benefits: screening out legislative candidates who see public service primarily or only as a means to personal gain; deterring corruption of the legislative process; and, perhaps most importantly, diminishing cynicism about legislative processes.

In an era when the President hides his tax returns from public scrutiny and retains beneficial stakes in his private businesses, more Congressional accountability is in the public interest.