Roadblock to Reform

How does politicized judicial selection affect whether judges implement criminal justice reforms?

Video: Roadblock to Reform

How do state court judges’ political incentives affect their willingness to employ criminal justice reforms? This report, Roadblock to Reform, looks at how judges in Kentucky and Virginia have adopted risk assessment tools to inform incarceration decisions. It considers whether judges’ willingness to use risk assessment tools is related to how the judge is selected.

Judicial Decision-Making in Kentucky and Virginia

The study shows that, in both states, reforms aimed at reducing incarceration for low-risk offenders had little to no impact on incarceration rates. While these tools clearly recommended less incarceration for a large share of defendants, they had little effect on judges’ incarceration decisions. However, there is tremendous variation among judges in how closely they follow the risk assessment recommendations.

Even in jurisdictions that require the use of these tools, the effectiveness of the risk assessments relies on how judges use the information provided to them. As is outlined in Roadblock to Reform, reforms that seek to reduce incarceration rates for low-risk offenders had little to no impact on incarceration rates in Kentucky and Virginia.

Findings in Kentucky and Virginia

Researchers decided to study Kentucky and Virginia because their reforms occurred at the statewide level instead of at the county level which ensures that there are many observations on which to base our analysis. In addition, both states began using algorithmic tools to aid in criminal justice decision making early on.

Kentucky has used some sort of algorithm to aid in the pretrial custody decision since the 1970s and made it mandatory in 2011. Virginia piloted risk assessment in the late 1990’s and adopted it statewide in 2002. Finally, both states adopted risk assessment with the explicit goal of reducing jail and prison populations.

The key findings of Roadblock to Reform reveal that many judges ignore the recommendations associated with the risk assessment tools.

As critics have pointed out, risk assessments are not perfect, but the report serves as an important warning that the pressures placed on judges by politicized selection and retention systems are a barrier to any meaningful criminal justice reform. We will never truly fix the criminal justice system unless we get politics out of the ways judges get and keep their jobs.

Thus, the Roadblock to Reform report shows that judicial selection reform is an important element of criminal justice reform and that citizens and policymakers can align judicial incentives so that reforms have their intended effects.

The Findings

Summary: Judges ignoring risk assessment recommendations

If Kentucky judges had followed the recommendations associated with the risk assessment in all cases, the pretrial release rate among low- and moderate-risk defendants would have jumped up by 37 percentage points after risk assessment was made mandatory. Instead, the pretrial release rate for low- and moderate-risk defendants increased by only 4 percentage points, from 63% to 67%.

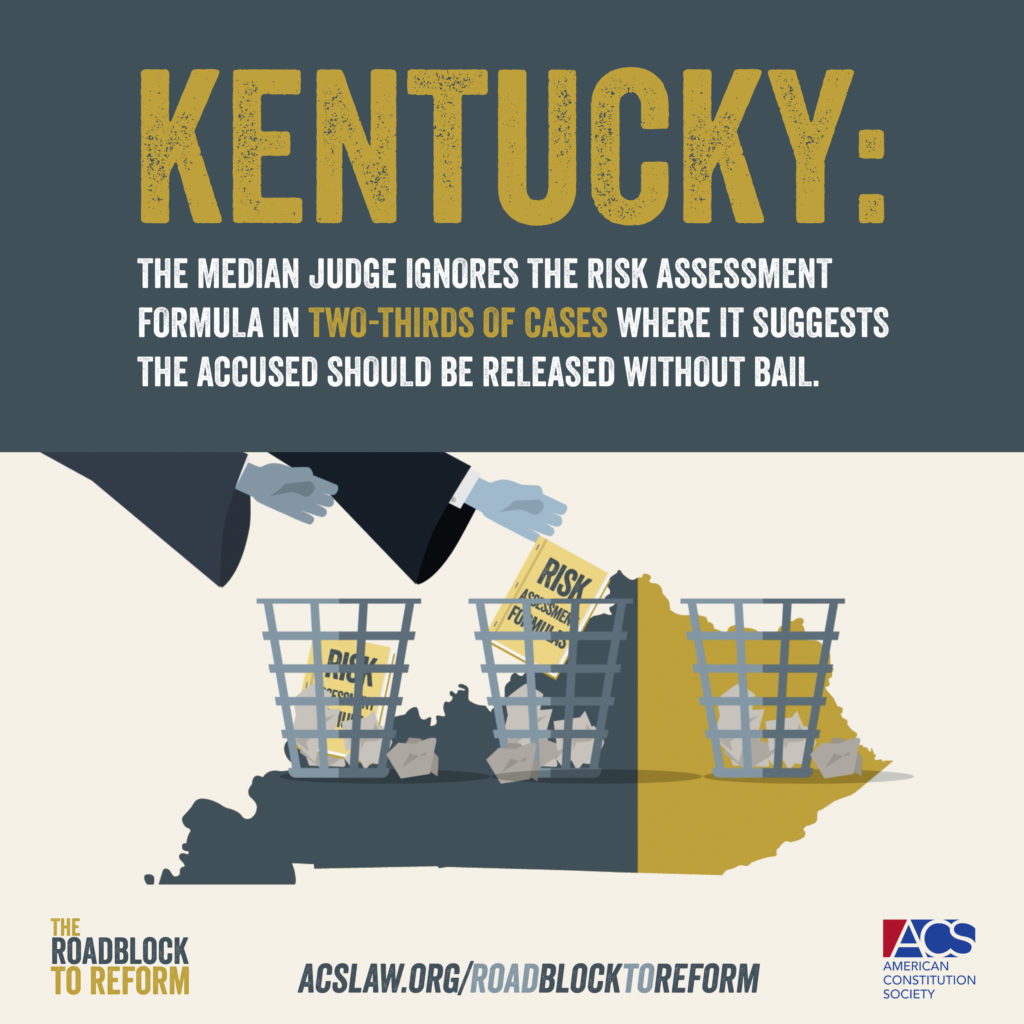

- The median judge in Kentucky grants release without monetary bail to only 37% of defendants with low or moderate risk status. In other words, the median judge overrules the presumptive default associated with the risk assessment about 2/3 of the time.

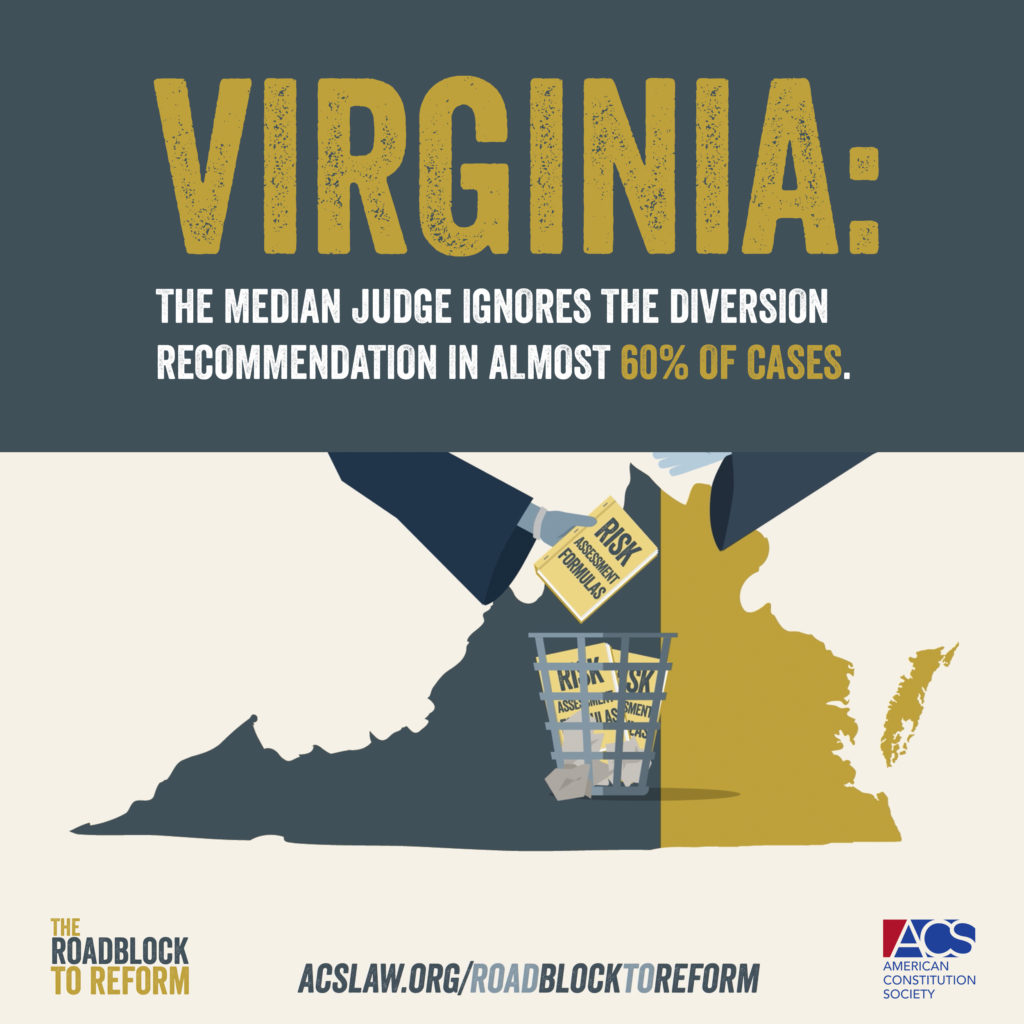

- If judges had followed the recommendations associated with the risk assessment, there would have been up to a 25% increase in the diversion rate among risk assessment-eligible offenders after risk assessment was adopted statewide. Instead, the diversion rate remained virtually unchanged, dipping just slightly from 34% to 33%.

- The median judge in Virginia diverts only about 40% of those who were recommended for diversion by the risk assessment instrument.

The Politicized System of Selecting State Court Judges

Judges are people. They come with their own beliefs about what kind of criminal justice response is appropriate in each particular circumstance. But being a judge is also a job. Understanding judicial incentives requires understanding the process by which judges are hired, retained, and promoted.

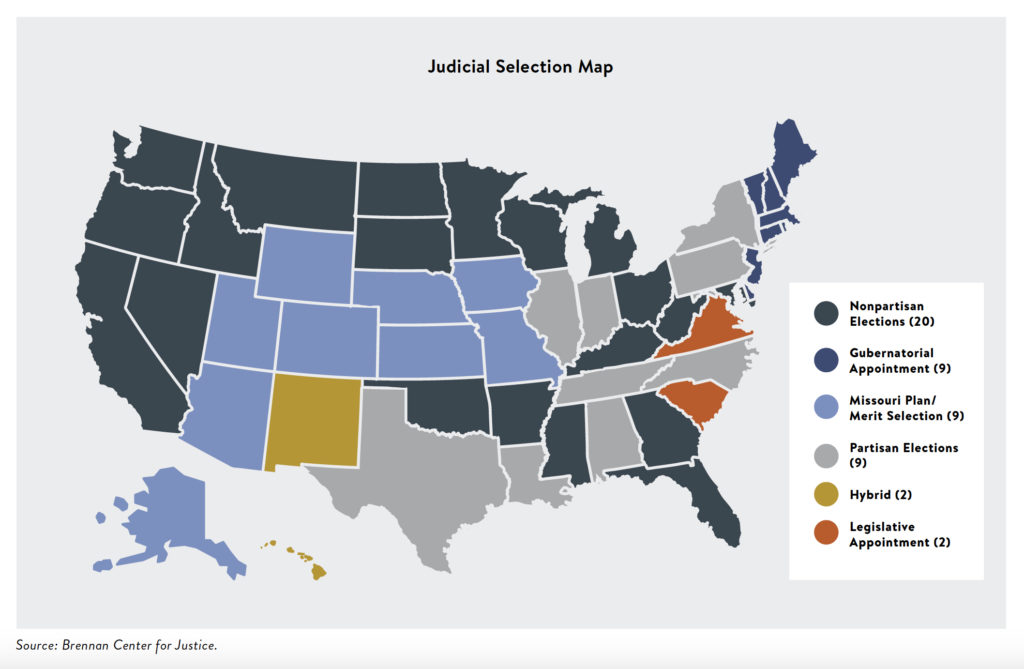

Almost all state court judges must obtain and keep their positions by means of highly politicized election and appointment schemes.

This is very different from the federal judicial system, in which, after judges are nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate, they become largely insulated from political pressure by lifetime terms.

Even after gaining office through election or appointment, almost all state court judges must routinely seek re-election or re-appointment on a regular basis. Trial court judges, who decide criminal cases, are often especially exposed to these political pressures.

Twenty-nine states elect their trial court judges, while two use a system of legislative appointment and reappointment. Such systems, combined with relatively short terms for most trial court judges, mean that judges are routinely confronted with the reality that voters or legislators will be passing judgement on their judicial records. The incentive to avoid being characterized as “soft on crime” – and thus at risk of losing their position–is powerful.

Report Authors

Megan T. Stevenson

Assistant Professor of Law at George Mason University

Jennifer L. Doleac

Associate Professor Of Economics at Texas A&M University, and Director of the Justice Tech Lab