January 17, 2019

The Barr Memo and the Imperial Presidency

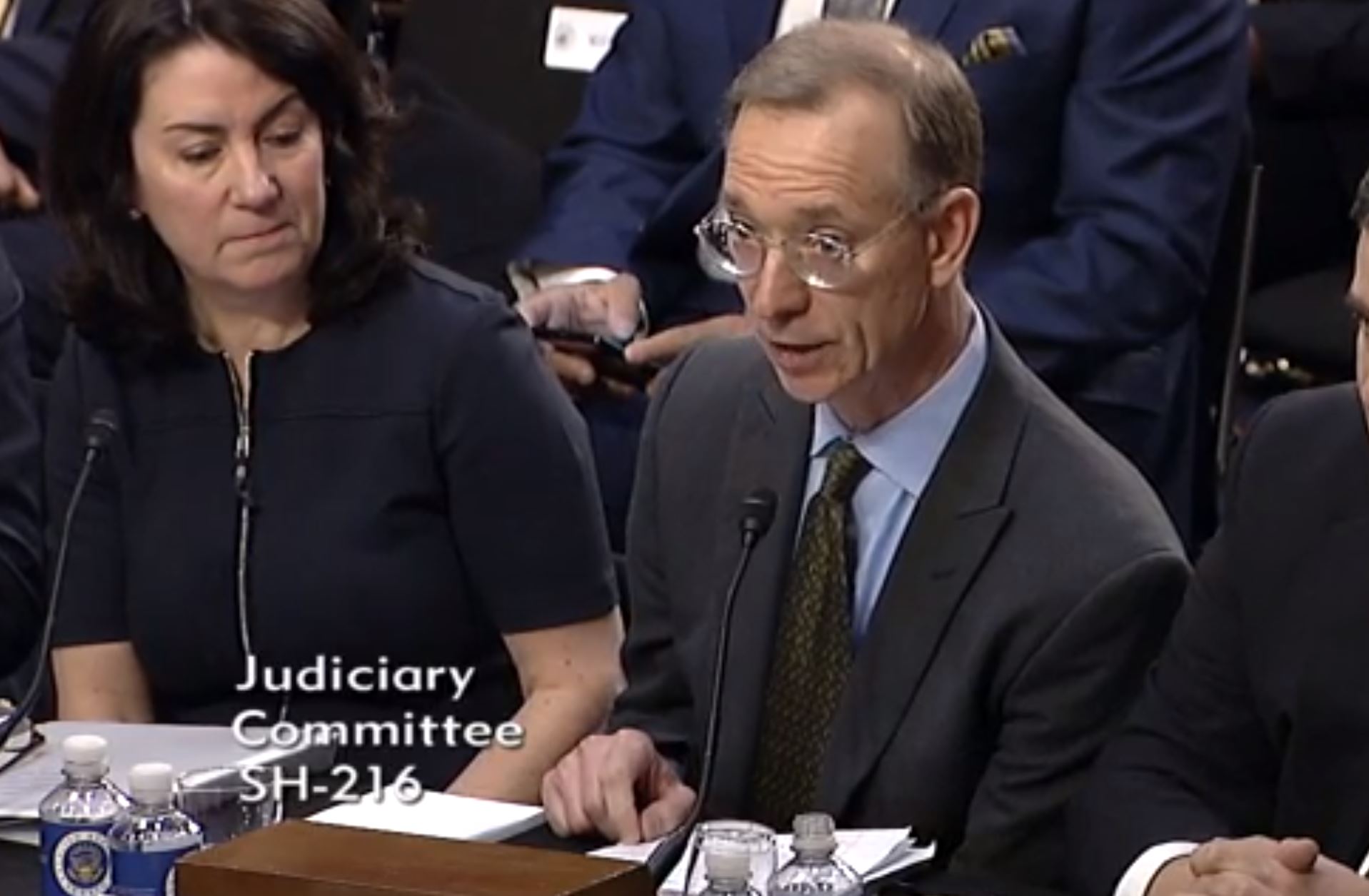

ACS Faculty Advisor and Professor of Law, Georgia State University College of Law

For more information on the Barr nomination from ACS, visit our resource page.

Last summer, William Barr wrote a memo for Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein and Assistant Attorney General for the Office of Legal Counsel Steve Engel. The memo had to do with the Mueller investigation and whether President Trump can be understood to have violated the obstruction of justice statute (spoiler alert: his answer was an emphatic “no”). Because William Barr is Trump’s nominee to be Attorney General, the memo has been the focus of attention for what it says about the Mueller investigation and for what it directly implies about that investigation (more spoilers: (1) Trump can take over, manipulate, or terminate the investigation, and (2) don’t hold your breath waiting to see a Mueller report).

If possible, I would like to focus attention elsewhere – on the ramifications of Mueller’s theory of the President’s constitutional powers for the rest of the government. Those ramifications are vast and proceed from the memo’s most jaw-dropping passage: “Constitutionally, it is wrong to conceive of the President as simply the highest officer within the Executive branch hierarchy. He alone is the Executive branch.”[1]

The conception of presidential power embraced in the Barr Memo goes well beyond the ordinary unitary executive claims. I have taken to calling it the imperial executive, in part because no Attorney General has ever come so close to accepting Louis XIV’s motto, “L’etat c’est moi.” This theory revives the view of executive power that launched a thousand signing statements, generated the torture memo, and justified warrantless domestic surveillance in spite of the legal prohibitions in the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. It is impossible to conceive of all the damage this theory will do in the hands of the Trump Administration, and a full catalog would require a book length post. I would, nonetheless, like to highlight a few implications that strike me as immediately obvious.

The independent agencies are unconstitutional. William Barr’s view of presidential power would hold independent agencies unconstitutional, overturning nearly a century of Supreme Court precedent and upending dozens of regulatory agencies. It would be shocking enough for the Barr Memo to assert that the Supreme Court’s most foundational decisions relating to the constitutionality of the regulatory state have been consistently wrong for nearly a century. The Barr Memo does not even note that it is irreconcilable with these decisions, let alone attempt to explain why they should be disregarded.

The Supreme Court has held that Congress may establish independent agencies – that is, agencies that exercise their power subject to the policies set forth in law and not subject to the President’s political oversight.[2] The mechanism that renders an agency independent in this sense is a limit on the President’s removal authority; the President may only remove the head(s) of an independent agency “for cause” rather than “at will.” As then-Assistant Attorney General for the Office of Legal Counsel William Barr put it, “Because the power to remove is the power to control, restrictions on removal power strike at the heart of the President’s power to direct the Executive Branch and to perform his constitutional duties.”[3] The Barr Memo does not mince words, the President “has illimitable discretion to remove principal officers carrying out his Executive functions.”[4] On this theory, the President may, for example, order the Chairman of the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates (or not) and then may fire the Fed chairman if he refuses to heed the President’s order. The President may order the Securities Exchange Commission to undertake certain enforcement actions, or to drop certain actions, and remove any commissioner who objects. The result would be a dramatic re-working of the administrative state, and a massive aggrandizement of the President’s power.

The Qui Tam provisions of the False Claims Act are unconstitutional. Then-Assistant Attorney General Barr composed a lengthy legal opinion expressing precisely this view in 1989.[5] He asserted, “the authority to enforce the laws is a core power vested in the Executive. The False Claims Act effectively strips this power away from the Executive and vests it in private individuals, depriving the Executive of sufficient supervision and control over the exercise of these sovereign powers. The Act thus impermissibly infringes on the President's authority to ensure faithful execution of the laws.”[6] He also argued that the qui tam provisions violate the Appointments Clause.[7] The Barr Memo’s commitment to the President holding “illimitable” power over all law enforcement actions on behalf of the United States makes it clear that he continues to view these provisions of the False Claims Act as violations of both the Appointments Clause and the clause vesting the executive power in the President.

The President may prohibit executive branch agencies from sharing information and reports with Congress. Mr. Barr, in 1989, castigated legislation that the required executive officials to submit reports concurrently to Congress. Such requirements, he claimed, “prevent[] the President from exercising his constitutionally guaranteed right of supervision and control over executive branch officials. Moreover, such provisions infringe on the President’s authority as head of a unitary executive to control the presentation of the executive branch’s views to Congress.”[8] Under this view, the President may order executive branch officials to withhold information or reports that do not support or otherwise accord with the President’s position on a range of issues, from military and foreign affairs policy to climate change.

The President, acting as Commander in Chief, may order the use of torture as an interrogation technique notwithstanding federal law prohibiting it. The Barr Memo repeatedly asserts that the President’s constitutional powers are illimitable. One of the President’s most significant constitutional powers is his authority to act as Commander in Chief. Under the Imperial Executive theory, then, no statute may limit the President’s discretion as Commander in Chief to determine by what means to interrogate enemy combatants. This is, in fact, precisely the legal theory of the infamous Torture Memo.[9]

The President, acting as Commander in Chief, may order warrantless domestic surveillance despite statutory warrant requirements such as the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. As with torture, the President’s Commander-in-Chief power includes the authority to engage in surveillance of the enemy. If this power is illimitable, as the theory of the Barr Memo holds, then Congress may not dictate how the President exercises it, even if that dictate is the protection that before engaging in electronic surveillance the executive first secure a warrant.

The President may initiate and prosecute a full-scale war without first receiving a declaration or authorization from Congress. The view of illimitable executive power expressed throughout the Barr Memo has been taken to support the claim that Congress’s power to declare war is irrelevant to the President’s power as Commander in Chief to order U.S. troops into combat, including foreign invasions that clearly constitute war in the constitutional sense.[10] On this view, the function of a formal declaration of war is limited to technical international law consequences and has nothing to do with the President’s power to go to war.

The President alone may determine the nation’s foreign policy. Since the founding, it has been understood that the President holds extensive power relating to the nation’s foreign affairs. Future Chief Justice John Marshall’s description of the President’s role, offered during a House of Representatives debate, endures, “The President is the sole organ of the nation in its external relations, and its sole representative with foreign nations.”[11] This expresses the broad consensus that the President speaks for the nation and serves as our chief diplomat. It does not, however, follow that the President is exclusively authorized to determine the content of the nation’s foreign policy. Indeed, numerous powers assigned specifically to Congress[12] appear plainly to contemplate a significant legislative role in this area. In a 1989 memorandum, Mr. Barr opined that “[i]t has long been recognized that the President, both personally and through his subordinates in the executive branch, determines and articulates the Nation’s foreign policy.”[13] This claim was based on broad dicta[14] that the Supreme Court has since repudiated.[15] As the views expressed in the 1989 Memo are consistent with the approach of the 2018 Barr memo – insofar as each minimizes or ignores the existence of relevant legislative powers – it appears that Mr. Barr continues to adhere to the position he expressed in 1989.

Statutes should be read to relieve the President of statutory obligations. The Barr Memo applies the so-called clear statement rule in a manner that grants the President a broad exemption from the obstruction-of-justice statute. According to the Barr Memo, “statutes that do not expressly apply to the President must be construed as not applying to the President if such application would involve a possible conflict with the President’s constitutional prerogatives.”[16] The Barr Memo ignores two predicates for the application of the clear statement rule: first, the statute must be reasonably susceptible of an interpretation that does not include the President; and second, the application of the statute must involve more than a hypothetical or “possible” constitutional conflict, it must create a serious and unavoidable constitutional conflict. Application of the obstruction of justice statute to the President satisfies neither of these predicates. Even more troubling is what this loose application of the clear statement rule would mean across the spectrum of federal statutes. The President would be exempt from broad swaths of federal criminal laws, not to mention civil and administrative statutory requirements.[17] As I have explained elsewhere, applied without rigorous application of its predicates, the clear statement rule “is a sort of magic wand that allows the lawyer wielding it to make laws (and legal constraints on the President) disappear.”[18]

This is not an academic concern. President Trump has made it clear that he plans to explore pursuing to their utmost his statutory emergency powers to deal with issues such as the government shutdown and the construction of a wall along the southern border. It is crucial that the Attorney General be committed to facilitating the President’s policy agenda in a manner that fully complies with federal law – both constitutional and statutory.

* * * * * *

We live in troubled times, marked by deep political divisions. In such times, it is especially crucial that our legal institutions remain anchored to sound legal principles. Our President has declared “I have [the] absolute right to do what I want to do with the Justice Department.”[19] Public confidence in the rule of law depends on there being an Attorney General who will not allow the President to do whatever he wants with the Justice Department. William Barr’s views of presidential power are so radically mistaken that he is simply the wrong man, at the wrong time to be Attorney General of the United States.

*Professor, Georgia State University, College of Law. Affiliation listed for identification only.

[1] Memorandum from Bill Barr to Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein and Assistant Attorney General Steve Engel, re: Mueller’s “Obstruction” Theory, at 9 (June 8, 2018)(emphasis in the original)(n.b. The Barr Memo is not paginated. Pin cites are therefore estimates).

[2] See Humphrey’s Ex’r v. United States, 295 U.S. 602 (1935).

[3] Common Legislative Encroachments on Executive Branch Constitutional Authority, 13 Op. O.L.C. 248, 252-53 (1989).

[4] The Barr Memo at 9.

[5] The qui tam provisions authorize private individuals, whistleblowers, with knowledge of fraud being perpetrated against the United States to bring claims against these perpetrators on behalf of the United States. This program has been remarkably successful in helping the federal government combat fraud.

[6] Constitutionality of the Qui Tam Provisions of the False Claims Act, 13 Op. O.L.C. 207, 210 (1989).

[7] Id. at 209-210.

[8] Common Legislative Encroachments, supra note 3, at 255.

[9] Memorandum for Alberto R. Gonzales, Counsel to the President, from Jay S. Bybee, Assistant Attorney General, Office of Legal Counsel, Re: Standards of Conduct for Interrogations under 18 U.S.C. §§2340-2340A (August 1, 2002). The Torture Memo was wrong for many reasons. The one most relevant here is that it ignored the existence of numerous powers authorizing Congress to enact the Anti-Torture Act, including Congress’s power to make rules for the government and regulation of the land and naval forces, to make rules regarding captures, and to define and punish offenses against the law of nations, as well as the Necessary and Proper Clause.

[10] See, e.g., Memorandum for Timothy E. Flanigan, Deputy Counsel to the President, from John C. Yoo, Deputy Assistant Attorney General, Office of Legal Counsel, Re: The President's Constitutional Authority to Conduct Military Operations Against Terrorists and Nations Supporting Them (Sep. 25, 2001).

[11] 10 Annals of Cong. 813 (1800).

[12] See, e.g., U.S. Const. art. I, §8, cl. 3 (regulate foreign commerce); id. cl. 10 (define and punish offenses against the law of nations).

[13] Common Legislative encroachments at 256 (emphasis added).

[14] See United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp., 299 U.S. 304 (1936).

[15] See Zivotofsky ex rel. Zivotofsky v. Kerry, 135 S. Ct. 2076, 2079 (2015).

[16] The Barr Memo at 6.

[17] See, e.g., Daniel Hemel and Eric Posner, The President Is Still Subject to Generally Applicable Criminal Laws: A Response to Barr and Goldsmith, Lawfareblog (Jan. 8, 2019).

[18] See Clear Statement: The Barr Memo is Disqualifying, Take Care Blog (Jan. 14, 2019). See also H. Jefferson Powell, The Executive and the Avoidance Canon, 81 Ind. L.J. 1313 (2006).

[19] Michael S. Schmidt and Michael D. Shear, Trump Says Russia Inquiry Makes U.S. “Look Very Bad,” N.Y. Times (Dec. 28, 2017).

Constitutional Interpretation, Executive Power, National Security and Civil Liberties, Regulation and the Administrative State, Role of Regulatory Agencies, Separation of Powers and Federalism, Surveillance and Privacy, War Powers