September 6, 2018

Kavanaugh Hearings Day Two: Dishonesty on Garza

Professor of Law, Associate Dean for Academic Administration and Strategic Initiatives, and Founder & Co-Director, Institute on the Supreme Court of the United States (ISCOTS), Chicago-Kent College of Law; Former Illinois Solicitor General

inbrief

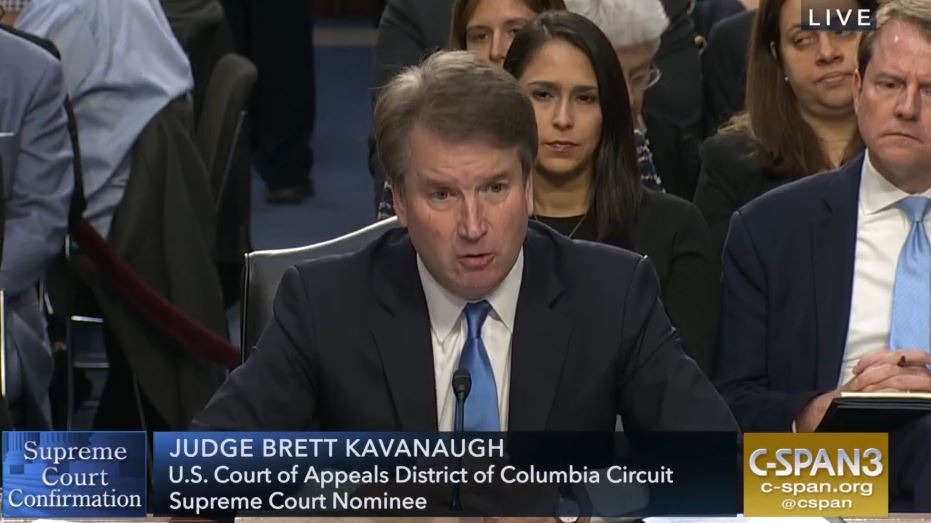

The first two days of the hearings on Judge Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination to the Supreme Court are over. Based on the parts I’ve been able to watch or listen to, and the commentary and reporting I’ve seen, three things stand out for me:

The missing and “committee confidential” documents are a very big deal. Democrats began the hearings yesterday with a coordinated and angry effort to expose the lack of transparency with respect to the documents produced – the lack of documents from Kavanaugh’s time in the White House, the Trump Administration’s claim of executive privilege over more than 100,000 documents, and the “committee confidential” designation on thousands of pages, thus precluding the senators from asking about them publicly. Here are four reasons that I am increasingly troubled:

- Senators Durbin and Leahy are not hotheads. They’ve been on the Senate Judiciary Committee for a long time. And both seem fairly sure that Kavanaugh lied to them during his 2006 confirmation hearing to the D.C. Circuit. Leahy in particular appeared very angry about not being able to question Kavanaugh about the “committee confidential” documents. (Those are the documents that have been produced to the committee but that cannot be made public.) I certainly am not prepared to say I think Kavanaugh lied, but Durbin and Leahy have presented a prima facie case that needs to be publicly addressed.

- Many documents have not been produced at all, in large part because of the committee’s rushed process that has sidelined the National Archives’ ordinary review of executive branch documents. The claim that the Republicans keep making in defense of this fact – that more documents have been released than for any other nominee – is laughably lame. The issue is not the raw number of pages. The issue is how much of the universe of relevant and non-privileged information is made available to the committee. If there are 10,000 pages of relevant documents, and 9,999 pages are produced, that’s suggests virtually everything has been produced. If there are 100,000 pages of relevant documents and 80,000 are produced – well, that’s eight times more than in the first example, but the increased raw number does not make it more satisfactory. And here, the percentages are much, much more skewed. Also, it’s hard to think of a good reason not to rely on the National Archives’ nonpartisan process.

- The Archives told the Committee that it would not be able to complete the review until late October. But that timing should not present a problem. There is no reason to rush. The Republicans kept Justice Scalia’s seat open for more than a year. I was among those who argued “we need nine,” and I still believe that. But I don’t believe that we need nine as of October 1. Any case that results in a 4-4 tie in October or November can easily be reargued during the very same Term.

- Senator Durbin asked Kavanaugh if he had any objection to the release of any of the disputed documents. He refused to answer, saying only that the document production issues were for the senators and the executive branch to work out. It’s true that Kavanaugh can’t require or prevent the production, but there’s no reason he can’t say that he has no objection. Why didn’t he?

Kavanaugh’s statements both in and about his opinion in Garza v. Hargan, involving the undocumented teenager who sought an abortion, are frankly dishonest. (Reminder about the facts: the teenager, Jane Doe, discovered she was pregnant after arriving in this country. As an undocumented minor, she was in the custody of the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR). Although she had third parties willing and able to transport her to all the medical appointments and to pay for the procedures, ORR refused to allow her to leave the facility she was staying in to get the abortion.)

- Yesterday, Kavanaugh described the case as being about parental notification. But Doe had already met the requirements of Texas law for a minor seeking an abortion without parental notification, and there was no federal parental notification policy in place, nor did the government say that it was defending one. There was no regulation, no enactment about parental notification. Instead, there was a government official – the head of ORR – who refused to allow any young women in ORR custody to get abortions.

- In his opinion, Kavanaugh described the issue as being about whether the government was justified in wanting Jane Doe to be “in a better place” – that is, with a sponsor (like a foster family) – before she had the abortion. But the government did not make this argument either Instead, the government argued that it should not have to “facilitate” the abortion by allowing Doe to be taken to the clinic by a third party and that Doe could always get the abortion by leaving the country or finding a sponsor. So the “better place” argument of Kavanaugh’s dissent was a fabrication.

- Yesterday, Kavanaugh suggested that his opinion made clear that the federal government would have to allow Doe to leave the shelter for an abortion if no sponsor was found by a particular date. But that’s not what the opinion said. It contained no such assurance.

- And then there is the timing. Before the Garza opinion, Kavanaugh was not on Trump’s list of potential nominees. Afterwards, he was. As Senator Blumenthal suggested, that looks like he was auditioning.

Kavanaugh’s views about unenumerated rights, like the right to privacy, are very crabbed. At the end of the day, Senator Kamala Harris asked Kavanaugh about Griswold and Eisenstadt. (Griswold struck down a law precluding married couples from using contraception; Eisenstadt extended the holding to unmarried people.) Kavanaugh’s answer was very troubling. He said that he agreed with Justice White’s concurrence in Griswold because it was rooted in a line of cases having to do with family autonomy. And in Eisenstadt, White declined to reach the question of unmarried individuals’ access to contraception. I hope that there will be some follow-up questions on this today.

Judge Kavanaugh did one important and good thing yesterday. He unequivocally embraced Brown v. Board of Education. To be honest, it is depressing to have to praise that embrace. But after Justice Gorsuch’s squirming on the question of Brown and Trump district court nominee Wendy Vitter’s absolute refusal to say whether it was rightly decided, Kavanaugh’s rejection of Jim Crow was a relief.