February 26, 2013

Private: Federalism and the Voting Rights Act

ACSblog symposium on Shelby County v. Holder, Bloody Sunday, Constitutional Interpretation and Change, Democracy and Voting, Election law, Gilda Daniels, Guest Post, Section 5, Shelby County v. Holder, Supreme Court, Voting Rights, Voting Rights Act, VRA

by Steven D. Schwinn, associate professor of law at the John Marshall Law School in Chicago and an editor of the Constitutional Law Prof Blog. This post is part of an ACSblog symposium on Shelby County v. Holder.

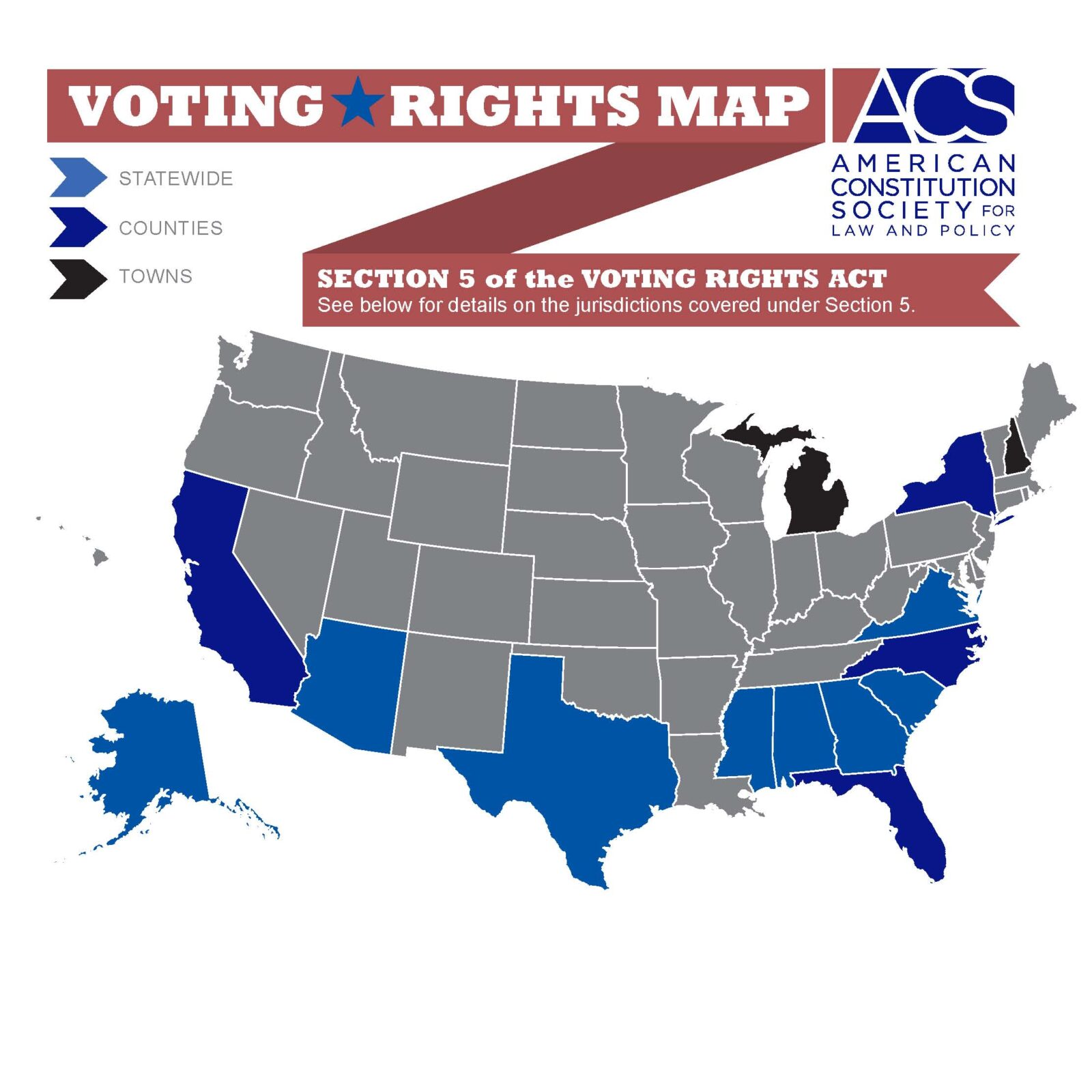

When the Supreme Court takes up the Voting Rights Act case this week, Shelby County v. Holder, the Justices will focus on this question: Whether Congress had authority under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to require certain jurisdictions to gain federal preclearance before making any changes to their election laws. But lurking in the background of the Question Presented is a curious nod to federalism. Thus the Court will ask if Congress exceeded its authority, then did it violate the Tenth Amendment and Article IV—provisions that, according to the petitioner, protect states’ rights.

We might wonder where this federalism concern comes from. After all, neither the Tenth Amendment nor Article IV limits federal authority because of states’ rights. Neither provision says anything about the substantive scope of federal authority; and neither provision obviously grants a claim of states’ rights. Instead, they simply outline the necessary relationship between the federal government and the states in a federal system like ours. These provisions are, at most, a blueprint for federalism. They add nothing to the core question of congressional authority, the real issue in the case.

Still, their presence in this case suggests a concern about federalism. That concern emerged most recently in the Court’s latest foray into the Voting Rights Act, Northwest Austin Municipal Utility District Number One v. Holder (2009), or NAMUDNO. The Court in NAMUDNO declined to rule on congressional authority to require preclearance, but it did mention that certain Justices had “misgivings about the constitutionality” of preclearance based on “federalism costs.” In other words, the Court in NAMUDNO suggested that federalism costs—the VRA’s encroachment on “states’ rights”—themselves could work to cabin congressional authority under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

This would be a strange result, indeed. That’s because the plain text of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments says that federalism concerns do not restrict congressional authority. Thus the Fourteenth Amendment says that “[n]o State shall” violate certain civil rights. The Fifteenth Amendment says that the right to vote “shall not be denied . . . by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Both Amendments contain an enforcement clause that says that “Congress shall have the power to enforce” the substantive terms of the Amendments. This is hardly the kind of language that reflects a concern about “federalism costs.”

That’s not surprising, given that the framers of the Amendments in the 39th Congress were anything but concerned about “federalism costs.” Indeed, they recognized and celebrated these “costs,” and used them as a reason to support the Amendments. Republican supporters of the Amendments specifically emphasized Congress’s vast new power to enforce civil rights—at the expense of the states. Opponents saw this, too. They worried that these Amendments would consolidate power in “one imperial despotism” that would “invade the jurisdiction of the States.” We know that supporters won that debate, and opponents lost, with their reasons and worries in full view. Both supporters and opponents knew that the Amendments fundamentally changed the nature of federal-state relations, and that they granted the federal government vast new authority at the direct expense of the states.

The Supreme Court, too, in its early cases on the Amendments, adopted this view. Thus the Court wrote in Ex Parte Virginia (1879) that the Amendments “were intended to be what they really are—limitations on the power of the States and enlargements of the power of Congress.” Even when the Court gave a crabbed reading to congressional authority in several early cases, perhaps most notably theCivil Rights Cases (1883), the Court was careful to limit congressional authority based on the substance of the Amendments, and pointedly not because of federalism concerns.

More recently, in South Carolina v. Katzenbach (1966) the Court upheld congressional power to enact preclearance in the first place. Like the early cases, Katzenbach did not define congressional authority in relation to the states, even though South Carolina pressed it. Indeed, Katzenbach said almost nothing about states’ rights or federalism costs. The Court in that case seemed to so take for granted the long-standing traditional view that it dismissed South Carolina’s federalism concern nearly out of hand.

This makes sense, given the Court’s approach to other federalism issues. For example, in an only slightly different context, the Court explained in Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer (1976) that the enforcement clause of the Fourteenth Amendment allowed Congress to abrogate a state’s Eleventh Amendment immunity from suit in federal court. The Court in that case said that the federalism concern, Eleventh Amendment immunity, was no concern at all, because the Fourteenth Amendment was designed to limit state sovereignty. If the Fourteenth Amendment allows Congress to work around the federalism concern of the Eleventh Amendment, surely it allows Congress to work around the federalism concern of the Tenth Amendment and Article IV. After all, as the text, framers, and earlier cases said, the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments revolutionized federalism by granting Congress vast new power at the direct expense of the states.

Thus the concern about “federalism costs” in NAMUDNO was until recently a distinctly minority one—a concern that consistently lost from the original debates through the more recent cases in the Supreme Court. The NAMUDNO Court itself recognized this: it cited a 1999 case that only loosely supported its “federalism concern”; and it cited no majority opinion, and principally dissents, to show that Justices have expressed “serious misgivings about the constitutionality” of preclearance. Moreover, it misread and misquoted its authority for its concern that preclearance violates the doctrine of equality of the states. In particular, the NAMUDNO Court suggested that the doctrine permitted congressional distinctions between the states to remedy local evils (and therefore that it might be used to overturn distinctions not properly tailored to remedy local evils). But in fact Katzenbach said the doctrine applies far more narrowly, “only to the terms upon which states are admitted to the union, and not to the remedies for local evils which have subsequently appeared.”

The Court’s “federalism concern” is no real concern at all. It is a position that lost in the original debates over the Amendments, lost in the early Supreme Court cases, and lost even in modern Court cases. It is only emerging now as a viable concern because that small group of dissenters who voiced it—those that the Court cited in NAMUDNO—happen to have a sufficiently strong voice on this Court. This is no reason reverse an approach to federalism and civil rights that has endured nearly 150 years. This is no way to make constitutional law.