March 20, 2012

Private: The Catholic Bishops Misunderstand Religious Liberty 1960-2012

Contraception, Griswold v. Connecticut, Religious liberty

By Leslie Griffin, Larry & Joanne Doherty Chair in Legal Ethics at the University of Houston Law Center

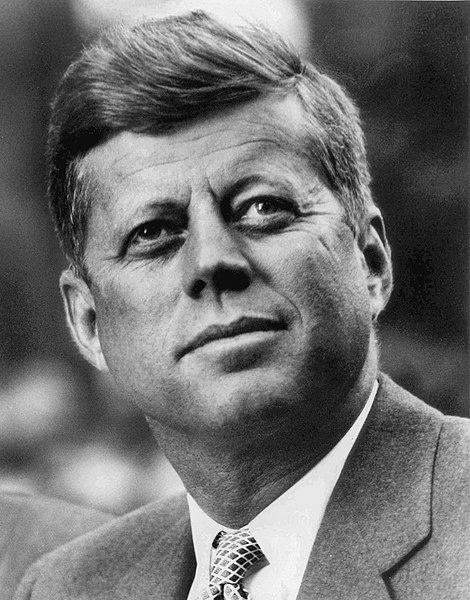

Before the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), the Catholic Church condemned the separation of church and state and taught that only Catholics had the right to public worship and religious liberty. In a series of nuanced essays written from 1940-1965, the New York Jesuit Catholic priest John Courtney Murray developed a historical argument that the prohibition on separation was not a timeless, universal norm, but was best understood as a response to the anticlerical liberalism of modern Europe. Hence, Murray concluded, American Catholics could favor the separation of church and state even though Rome (mistakenly) opposed it. Senator John F. Kennedy consulted Murray as he prepared his famous 1960 campaign address to Houston Baptist ministers pledging his commitment to the separation of church and state. The speech set the stage for Kennedy’s election as the first Catholic president of the United States.

The bishops of the Roman Catholic Church approved the Declaration on Religious Freedom, Dignitatis Humanae (DH), at the last session of the Council in December 1965. DH changed prior Catholic teaching by affirming that religious liberty is the right of every human person, not a right of Catholics only. Murray was the lead drafter of the declaration.

The bishops of the Roman Catholic Church approved the Declaration on Religious Freedom, Dignitatis Humanae (DH), at the last session of the Council in December 1965. DH changed prior Catholic teaching by affirming that religious liberty is the right of every human person, not a right of Catholics only. Murray was the lead drafter of the declaration.

Murray told reporter Robert Blair Kaiser in 1965 that the “resolution of the religious liberty issue had ‘transferential implications’ for those trying to work out the birth control question.” The “birth control question” asked if the church should revise its prohibition on artificial contraception. After extensive debate and reports from a papal commission, the church did not do so. Pope Paul VI instead reaffirmed the immorality of contraception in his 1968 papal encyclical Humanae Vitae (HV).

HV is the intellectual source of the Catholic Church’s current battle with the Obama administration over the provision of contraceptive insurance to its Catholic and non-Catholic employees. The church teaches that contraception is morally wrong as a matter of natural law for all men and women, Catholic and non-Catholic, married and non-married, without regard to whether they choose to believe or accept the teachings of the Catholic Church.

No one doubts that the bishops are sincere in their commitment to the anti-contraception moral principle. They are mistaken, however, to believe that the religious freedom protected by the U.S. Constitution entitles them to enforce their moral beliefs on others through force of law. Murray and Kennedy had a better sense of what the Constitution protects.

At a time when Kennedy’s vision of the First Amendment is under attack by the leading Catholic contender for the presidency, Senator Rick Santorum, it is worth remembering why Murray and Kennedy supported the religious pluralism protected by the First Amendment rather than the bishops’ view that their morals should govern everyone.

Murray’s experience as an American priest defending the First Amendment to a Roman audience taught him two important points about morality and religious freedom that bear repeating today, when women’s legal rights to contraception are under siege. First, contraception is a matter of private, not public, morality, and therefore should not be regulated by law. Second, laws restricting the right to contraception restrain religious freedom.

Murray developed those two ideas in the context of efforts to decriminalize contraception in Massachusetts. He wrote a 1965 letter to Boston's Richard Cardinal Cushing that addressed the proposed changes in Massachusetts law. Under existing law, anyone who sold or distributed contraceptives, or who advertised or disseminated information about contraception, could be fined or imprisoned. Murray supported the new proposal, which allowed doctors to prescribe contraception and health personnel to distribute contraceptive information to married persons. According to Murray, civil law should not “prescribe everything that is morally right and . . . forbid everything that is morally wrong.” Instead, civil law protects public morality and private morality is “left to the personal conscience.” In particular, civil law should not be used to enforce moral norms about which members of the community disagreed. Then as now, religious people of good faith disagreed about the morality of contraception. Thus it was wrong for the civil law to impose one moral view on everyone.

Relying on DH, Murray made a second argument about religious liberty and contraception. According to DH, a government may restrain an individual from following her conscience only when her action threatens the civil order, public peace or public morality. Contraception, however, was a matter of private morality; its use did not threaten public order. Because the government may not restrain its citizens from acting according to conscience on a private matter, Murray concluded, “laws in restraint of the practice [of contraception] are in restraint of religious freedom.” In the past, Catholics might have favored laws in restraint of contraception because they were consistent with the Catholic religion. Because of DH, however, Catholics should realize that non-Catholics had an equal right to religious freedom, i.e., to practice contraception without undue government interference.

Although Murray recognized the inherent difficulty in this position for Catholics, he insisted that Catholics should both live according to the church's teachings and support laws that permitted contraception. Moral law (no contraception) differed from civil law (no enforcement of private morality). Furthermore, government intrusion upon the moral law violated religious freedom. The Cushing letter’s final paragraphs express Murray's respect for law, morality and religious freedom, and reflect his nuanced account of the relationship among them:

Perhaps the essential thing is to make clear: (1) that from the standpoint of morality Catholics maintain contraception to be morally wrong; and (2) that out of their understanding of the distinction between morality and law and between public and private morality, and out of their understanding of religious freedom, Catholics repudiate in principle a resort to the coercive instrument of law to enforce upon the whole community moral standards that the community itself does not commonly accept.

As a good politician, John F. Kennedy made this point much more directly when he pledged that presidential decisions on birth control would be made according tothe national interest and “without regard to outside religious pressure or dictates.” Indeed, Kennedy promised to resign rather than enforce the church’s teaching and pictured an America where no Catholic prelate would tell the President how to act.

Today, Catholic bishops who have forgotten Kennedy’s and Murray’s principles loudly tell a non-Catholic president how to act. President Obama’s regulation requiring all employers to provide contraceptive coverage allows individuals to decide as a matter of conscience whether to use contraception, or not. The president’s policy is clearly in the national interest, as it protects women’s well-being in reproductive health, planned pregnancies and equal access to insurance in a manner recommended by the Institute of Medicine and other national health groups.

In contrast, by demanding that their employees be exempt from the law that applies to everyone else, the bishops “resort to the coercive instrument of law to enforce upon the whole community moral standards that the community itself does not commonly accept.” In direct defiance of the Free Exercise Clause, church employers seek to become a “law unto themselves” in the area of contraceptive insurance. The Catholic organizations covered by Obama’s regulation employ large numbers of non-Catholic and Catholic women, all of whom enjoy a constitutional right to contraception regardless of their churches’ teachings. Having failed since 1968 to persuade most Catholic women to avoid contraception, the bishops now claim the right to control their Catholic and non-Catholic employees’ access to health care by insisting that religious freedom entitles them to disobey the laws that govern similar employers.

Under Griswold v. Connecticut, sexual privacy, including contraceptive use, enjoys constitutional protection. Lawrence v. Texas reaffirms that the states may not intrude upon privacy because of a vague interest in protecting morality. The Supreme Court's decisions on privacy, old and new, echo Murray’s argument that the civil law should not regulate private morality. The principle remains the same as in Murray’s and Kennedy’s day although the specific details of the contraceptive laws have changed. The prelates should not be allowed to determine what law applies to everyone or to enforce their own morality through the coercive use of the law.

Constitutional Interpretation, Equality and Liberty, First Amendment, Women's rights