February 14, 2019

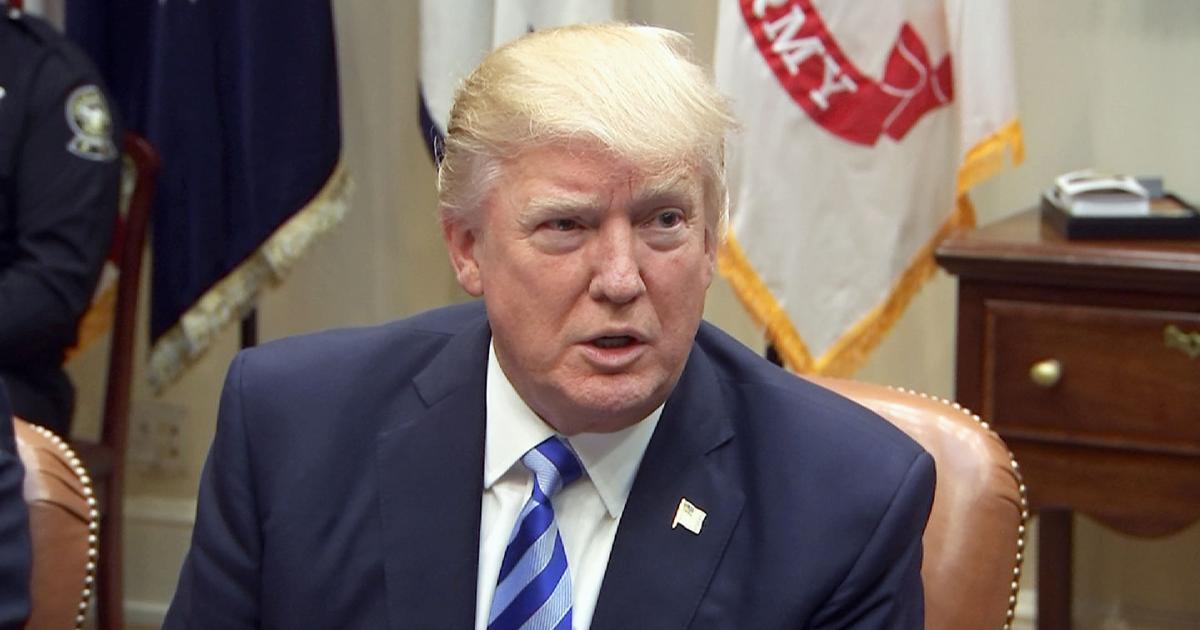

If Trump Takes Unilateral Action on Wall, Constitutional System Will Be Tested

Assistant Professor of Government, American University School of Public Affairs

It must be emphasized that this is not a done deal, but it appears likely that the president will sign into law legislation funding the federal government until the end of September 2019. When and if this legislation is enacted, federal workers who recently endured a 35-day partial government shutdown will undoubtedly heave a sigh of relief. But the issue that sparked the shutdown in the first place—President Trump’s demand for billions of dollars to support some construction of a new border wall between the United States and Mexico—will not go away. In fact, it remains possible that Trump will move ahead with his long-telegraphed threat to declare a national emergency in an effort to gain access to funds needed for wall construction.

This remains speculative, and it is of course possible that Trump will not declare an emergency. There are reports that Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell has warned the president not to do so, in part by telling Trump that congressional Republicans might take action to reject a presidential declaration of emergency. However, the president continues to suggest he might take unilateral action, claiming that “[w]e have options that most people don’t understand.” Those options could include declaring an emergency pursuant to the National Emergencies Act of 1976 or issuing an executive order to reprogram money already appropriated by Congress.

If the president does take unilateral action in an effort to free up money to build a new wall on the southern border, the constitutional system itself will be tested. The Constitution was designed to strike a balance between power and limits—to create a federal government strong enough to carry out the responsibilities assigned to it, while also setting limits to prevent that government, or any part of it, from gaining too much power. As James Madison wrote in Federalist 47, “[t]he accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands, whether of one, a few, or many…may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny.” Madison expected that members of each branch of government would jealously defend their branch against encroachment by another branch. For instance, members of Congress would act to rein in a president bent on consolidating power in his or her hands. This is the concept of separation of powers that undergirds constitutional democracy in the United States. It is built on overlapping authority—checks and balances--that, in theory, allows each branch of government to fulfill its duties without gaining a monopoly on powers

The problem, of course, is that the system only works if members of each branch take action when the balance of power is threatened. One way the system can fail is if members of Congress value partisan ties to a president of their own party above institutional power.

In the past, the system has worked when members of Congress and judges have put aside partisan or personal feelings to set limits on presidential power. For example, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed his court-packing plan, it was derailed when congressional Democrats saw this as a dangerous attempt to install pliant justices on the Supreme Court. When President Richard Nixon brazenly sought to undermine the rule of law, congressional Republicans joined Democrats in making clear that he faced a choice: resign from office or be removed through the impeachment process.

But, when presidents seek to set aside limits on their power, there haven’t always been happy endings. Five years after his court-packing plan went by the boards, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which paved the way for the internment of more than 100,000 Japanese Americans living on the west coast of the United States. Legislators and judges largely fell in line behind the president, providing legal cover for his actions, including in two Supreme Court decisions.

The shameful history of the Japanese American internment is instructive now for at least two reasons. First, it provides evidence that checks and balances only function when each branch of government takes action to set limits on power. Second, it reminds us that presidents can create contrived emergencies to justify assaults on the constitutional order. The executive branch sought to justify the mass internment of Japanese Americans in part by falsely claiming there was no time to separate supposedly disloyal Japanese Americans from the majority who were loyal. In fact, there was no evidence any were disloyal—and, as Justice Frank Murphy pointed out in his dissent from the 1944 Korematsu case, the emergency claim was a pretext. Roosevelt did not sign Executive Order 9066 until more than two months after the December 7, 1941 attack at Pearl Harbor, and internment was not completed until October 1942. As Murphy wrote, “Leisure and deliberation seem to have been more of the essence than speed.” There was no actual sense of urgency in taking action to place Japanese Americans in internment camps—unsurprisingly, as they did not actually pose a threat.

If Trump does ultimately seek to declare an emergency as a basis for gaining access to funds he wants for wall construction, it would be similarly clear that this is a pretext. Actual emergencies demand immediate action, not months (or years) of equivocation and delay. What’s really driving Trump is frustration at his inability to convince members of Congress (including Republicans) to appropriate money for his desired project. What would make it especially dangerous for Trump to take unilateral action is his authoritarian, anti-democratic tendencies and instincts. Political scientists Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt write that “[o]ne of our greatest concerns about Donald Trump’s presidency has always been that he would exploit (or invent) a crisis in order to justify an abuse of power.” If Trump takes unilateral action in an effort to make an end run around congressional refusal to provide the funding he seeks, the most important question will be whether congressional Republicans take action to stop him.

Chris Edelson is an assistant professor of government in American University’s School of Public Affairs. He is the author of Emergency Presidential Power: from the Drafting of the Constitution to the War on Terror.