May 11, 2023

What History Teaches Us About “Critical Race Theory” Bans

Director of Policy and Program for Racial Justice

Since the murder of George Floyd in 2020 and the mass protest movements that followed it, Americans of all colors have begun to pay renewed attention to the deep history of racial injustice in the United States and its ongoing negative effects for people of color. Majorities of Americans of all ethnic backgrounds now believe that systemic racism exists, and that society should work to address the ongoing impacts of discrimination.

Despite this growing consensus (or perhaps because of it), right wing operatives have launched more than 600 local, state, and federal initiatives to suppress free discussions about race and racism in the nation’s schools, universities, and private businesses over the past three years. While these measures vary in their substance, many share a focus on censoring a vaguely defined set of “divisive concepts,” including the very notion that racism is systematic in nature.

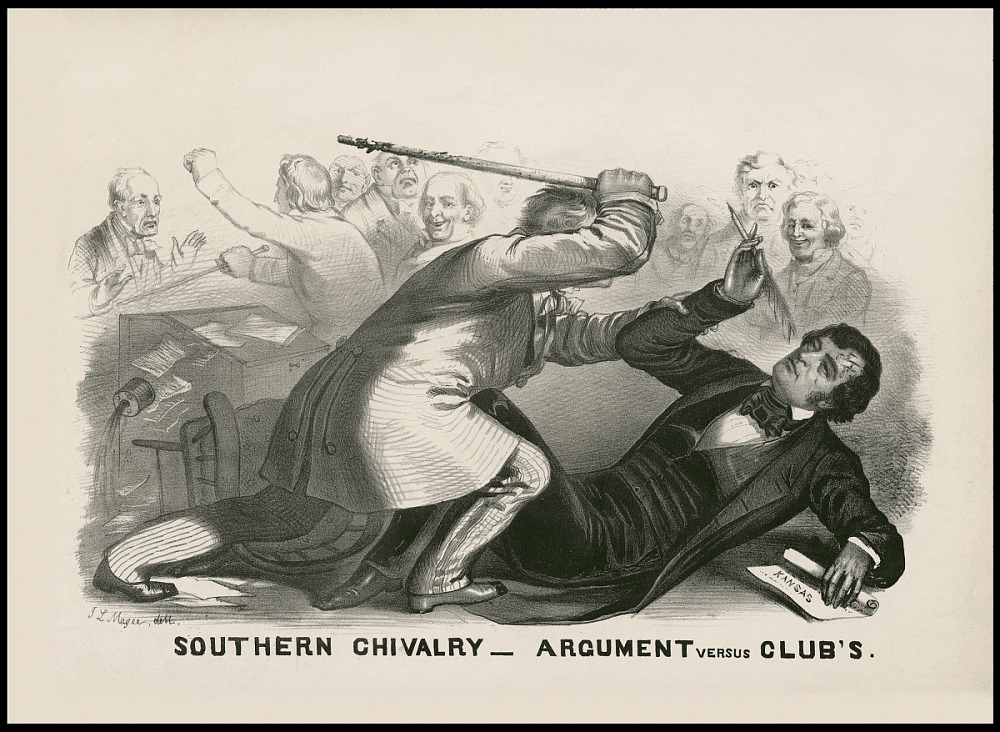

In suppressing discussion and debate about the nature of racial oppression in the U.S., right-wing leaders and operatives are drawing upon strategies first developed in the antebellum South to suppress criticism of slavery and targeting precisely the kind of speech the framers of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments sought to protect after the Civil War.

Abolition: the Original “Divisive Concept”

Just as George Floyd’s murder and the social movements it sparked drew increased attention to racial injustice in 2020, abolitionist movements began to raise existential questions about slavery in the United States in the late 1820s and 1830s.

A key development in abolitionist thought was David Walker’s 1829 “Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World.” In blistering terms addressed directly to other free and enslaved Black peoples, Walker excoriated the hypocrisy of America’s failure to uphold the ideals of the Declaration of Independence (“compare your own language … with your cruelties and murders inflicted by your cruel and unmerciful fathers and yourselves on our fathers and on us”) and connected the dots between the exploitation of enslaved people and the enrichment of the nation (“The greatest riches in all America have arisen from our blood and tears”).

Most crucially, the Appeal broke from prior anti-slavery writings by calling for the immediate abolition of slavery and for Black Americans to be treated equally within the United States, rather than the then-mainstream approach of the American Colonization Society which called for Black Americans to be gradually emancipated and resettled to other territories.

Walker’s words caused an immediate stir across the country, and while his views were initially deemed radical, even by many Black readers and white allies, they helped to influence a new generation of advocates including Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison. In 1833, Garrison helped co-found the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS), which took up Walker’s call for immediate and total abolition of slavery—and quickly began to supplant the American Colonization Society as the nation’s leading anti-slavery voice. By 1835, the AASS had launched a national pamphlet campaign aimed at raising the moral consciousness of white Southerners.

Even in the deep South, Walker’s and others’ criticisms of slavery moved some to question the legitimacy, or at least the sustainability of the slave system. In 1831, in the wake of Nat Turner’s rebellion, which many linked to the Appeal, approximately 2,000 Virginians petitioned their state legislature to end slavery, with some describing the institution as a violation of “the first principles” of American democracy as well as “the immutable laws of justice and humanity.” A bill that would have gradually ended slavery in Virginia narrowly failed in the 1832 legislative session.

The South’s Censorship Campaign

While growing criticism of slavery moved some to question the status quo, it motivated other Southern politicians to stamp out critical conversations about slavery entirely. In 1829, shortly after the publication of Walker’s Appeal, Georgia passed a law making it a crime to instruct a person of color to read or write. Virginia and Alabama passed similar laws in 1831 and 1833. After the AASS began its 1835 mass mailing campaign directed toward white Southerners, Southern states responded by expanding the scope of censorship. In 1836, Virginia passed a law criminalizing speaking, writing, or publishing “incendiary doctrines” including the notion that people did not have the right to own slaves or that slaves had the right to rebel. The following year, Missouri’s general assembly passed a law to prohibiting “the publication, circulation, and promulgation of the abolition doctrines.”

Southern fervor against the “incendiary doctrine” of abolition was so strong that Southern states petitioned the federal government to suppress abolitionist doctrines being sent by mail, and even called upon Northern states to take steps to suppress abolitionist speech. In practice, preserving the institution of slavery would require suppressing the free speech rights of free and enslaved people of all colors.

After the Civil War, the framers of the revised Constitution saw abolition and free speech as inseparable virtues. As Sen. James Harlan put it, “slavery cannot exist, when its merits can be freely discussed.” John Bingham, the drafter of the 14th Amendment, drew on the experience of Southern suppression of free speech as a key argument for its passage, declaring “the American people cannot have peace, if, as in the past, States are permitted to take away freedom of speech, and to condemn men, as felons, to the penitentiary for teaching their fellow men.” In their eyes, defending the rights of all Americans would require being able to speak freely and openly on the most pressing injustices facing the nation.

Today’s Battle for Free Discourse on Racial Justice

Today’s efforts to limit free discourse and education about the role of race in American history bear striking parallels to the slaveowners' efforts to outlaw dissent and maintain ignorance among populations they desired to control. Current measures targeting “divisive concepts” might as easily apply to some of the rhetoric that the abolitionists used to rally their audiences against slavery.

Teaching William Lloyd Garrison’s famous assertion that the Constitution was a “covenant with hell” (due to provisions like the Three-Fifths compromise which protected slavery) would arguably run afoul of new Iowa standards censoring the concept that the United States is “systematically racist.” Similarly, teaching the abolitionists' broadsides against slaveowners might violate new Tennessee standards prohibiting “division between or resentment of... a social class.”

Unfortunately, due to the inherent vagueness of these standards and the consequences of violating them, many educators are now afraid to speak out on some of the most important topics of our times—according to a recent national survey of educators, nearly 1 in 4 educators have altered or moderated their lesson plans for fear of broaching topics that parents or officials might deem controversial.

Free speech remains a key tool in the ongoing struggle for true equality. As history informs us, the stigmatization of “divisive concepts” is too often a tool for suppressing dissent and reinforcing unfair power structures. Just as slavery could not exist when discussed freely, critical education and debate about current forms of exclusion and exploitation is one of the surest tools in our continued liberation.

Constitutional Interpretation, Equality and Liberty, First Amendment, Racial Justice