July 18, 2014

Private: Compromise and the Civil Rights Act of 1964

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Freedom Summer and Civil Rights Symposium, Gaberial J. Chin, Gabriel J. Chin, income inequality, LGBTQ equality

by Gabriel J. Chin, Professor of Law, UC Davis School of Law

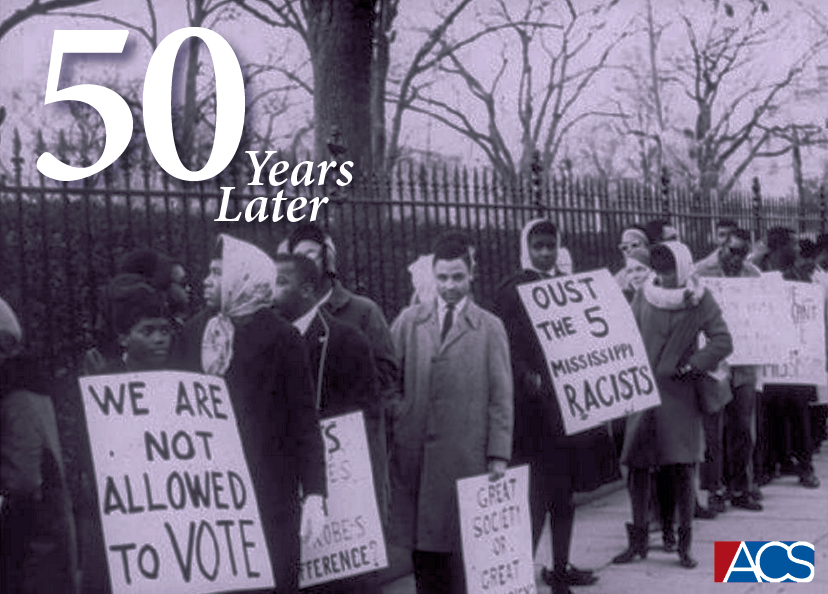

*Noting the 50th anniversaries of Freedom Summer and the Civil Rights Act of 1964, ACSblog is hosting a symposium including posts and interviews from some of the nation’s leading scholars and civil rights activists.

Practicing the art of the possible rather than seeking perfection may be an inevitable feature of civil rights legislation. Even the greatest and most honored laws have loopholes; the Thirteenth Amendment, for example, allows slavery based on conviction of crime, any crime, and the exception was liberally exploited in the former Confederacy after Redemption. The Fifteenth Amendment seems to countenance discrimination on the basis of sex, and a protection in earlier versions of the right to hold office was stripped out before enactment.

Nevertheless, I’ll take them; I do not criticize the Reconstruction Amendments or their makers for being merely as good as was possible at the time. Similarly, it would not have been better to give up what was good in the 1964 Act simply because of its deficiencies. At the same time, recognizing a law’s compromises and gaps is essential to understanding its real import, and to thinking about how policy can be shaped to fully reflect the principle at stake.

Among the important compromises in the bill are exemptions from the employment discrimination prohibition of Title VII for businesses of less than 15 people, and the exemption from the Public Accommodations provision of Title II for small, owner-occupied motels and lodging establishments. Presumably, these exceptions exist for the benefit of racists who grew up in a racist system through no fault of their own. Congress might reasonably have concluded that forcing close contact between racial minorities and these racists might have been more trouble than it was worth. But these exemptions should have been time-limited; at this point, all but the oldest business owners spent their entire lives, or at least their adulthoods, in a nation were discrimination has clearly been against the law and public policy. The case for continued compromise of the policy is not obvious.

Another major gap in the Civil Rights Act is the lack of protection against discrimination of members of the LGBTQ community. Clearly, this was no oversight. The desegregation struggle was to some degree a Cold War propaganda effort. Fair treatment on the basis of race was a “cold war imperative,” and so too was controlling the potentially subversive effects of sexual minorities. Thus, the 1965 Immigration Act, a close cousin of the Civil Rights Act, eliminated discrimination on the basis of race in immigration law, but simultaneously clarified and strengthened a prohibition on gay and lesbian immigration. The Civil Rights Act makes little sense unless it recognizes a fundamental human dignity and equality. The Americans with Disabilities Act and the Age Discrimination in Employment Act closed unjustified gaps in the coverage of the original law, and the prohibition on gay immigration is gone. Continuing to allow discrimination against gays and lesbians in the Civil Rights Act is indefensible.

Perhaps the biggest compromise in the Civil Rights Act was its forward-looking, non-remedial nature. Congress recognized that there had been discrimination in employment, public accommodations, and federal programs for decades, at least, and, as a result, vast disparities between racial groups with respect to education, income and wealth. But it addressed that problem by trying to create a level playing field going forward. It expressly did not require affirmative action. And even its levelling of the playing field was incomplete; Title VII immunized “bona fine seniority” systems, even if whites benefitted because of pre-Act discrimination.

I do not know whether Congress and the President thought formal equal opportunity would be enough to create a society where it would become harder to predict the life course of a newborn simply by knowing her race. For all that it did accomplish, and without questioning is historic nature, the Civil Rights Act was just a step toward ending the racial caste system in the United States, not a silver bullet that could do the job all by itself.

The renewed discussion of income inequality in the United States may be a way of getting at the unfinished business of the Civil Rights Act. It turns out that children who have advantages like housing, medical care and quality education are in fact permanently advantaged in terms of measures like income. A new Civil Rights Act would make sure that all children, of whatever race, had a fair opportunity for education, including higher education, regardless of their family’s income.

Constitutional Interpretation, Democracy and Elections, Equality and Liberty, Racial Justice, Voting Rights