July 14, 2014

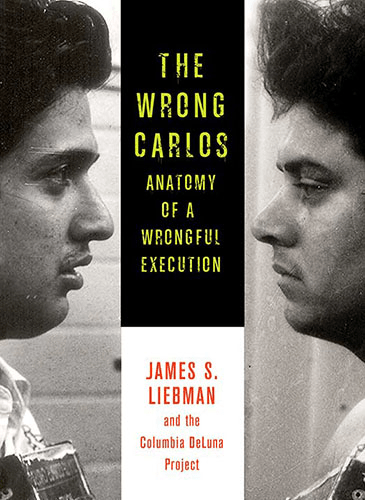

Private: The Wrong Carlos: Anatomy of a Wrongful Execution

James S. Liebman

by James S. Liebman, Simon H. Rifkind Professor of Law, Columbia Law School, and Shawn Crowley, Andrew Markquart, Lauren Rosenberg, Lauren Gallo White and Daniel Zharkovsky

Do states with the death penalty execute innocent people? That is the fundamental question at the heart of The Wrong Carlos, a book I recently published with student coauthors.

It is also the question facing the American public following a series of devastating developments for death penalty supporters. March brought news of the 144th death row exoneration. In April, we learned that Oklahoma had botched Clayton Lockett’s execution, leaving him awake during a massive drug-induced heart attack. The Supreme Court found in May that Florida remains hell bent on executing defendants too mentally disabled to be condemned. And in June—for the first time—a majority of Americans indicated in a poll that they prefer life without parole to capital punishment.

Death penalty supporters are left clinging to a single promise often made but never substantiated—a promise repeated by Justice Scalia in a 2006 opinion: Whatever else we do, we don’t execute the innocent.

I began thinking about this question between 2000 and 2003, when colleagues and I issued our Broken System studies documenting judicial findings of accuracy-impugning error in two-thirds of all U.S. capital cases reviewed between 1973 and 1995.

Our studies sparked a heated debate over two competing interpretations. Did the courts’ discovery of so many errors prove the system worked? Or do high error rates mean it is almost certain that courts miss other errors, allowing the innocent to be executed?

Starting in 2003, Columbia Law School students joined me in searching for a criminal prosecution and execution to shed light on this debate. We looked in Texas, where by far the largest number of American executions occur, and, in particular, at cases involving the always alluring but often unreliable testimony of eyewitnesses. The 1989 execution of Carlos DeLuna fit the bill: his conviction for the murder of a gas station clerk named Wanda Lopez rested on a single eyewitness identification. Meanwhile, DeLuna always maintained that another Carlos—an acquaintance named Carlos Hernandez—had actually committed the crime.

At trial, the prosecution assured the jury that it had diligently searched for “Carlos Hernandez” and that he was a “phantom” DeLuna had invented. DeLuna’s habeas judge and the governor’s clemency counsel were likewise convinced Hernandez “never existed.” Less than seven years after the crime, Texas executed DeLuna.

We asked a private investigator named Peso Chavez who was in Corpus Christi on another case to spend a few spare hours looking for Carlos Hernandez. Chavez’s tantalizing discovery—and the painstaking multi-year investigation that followed—made clear that the phantom in the Carlos DeLuna case was not Carlos Hernandez.

The phantom was justice.

Police records showed Hernandez not only existed but had terrorized Corpus Christi’s bay-front Hispanic neighborhood for years before and after the gas-station killing; was (as a relative described him) a dead “ringer” for Carlos DeLuna; and repeatedly told relatives, neighbors, and informants who told the police that it was he, not his “tocayo” (twin) DeLuna, who killed the gas station attendant.

Everything that can go wrong in a capital case did go wrong in DeLuna’s—from the original police investigation to the execution itself. Several minutes into DeLuna’s Dec. 7, 1989 “lethal injection”—long after he was supposed to be unconscious and as a painful, heart-attack-inducing drug began flowing into his veins—DeLuna sat up. Just as Clayton Lockett did in April, DeLuna fearfully looked an attending witness in the eye.

In the epilogue of The Wrong Carlos, my students and I hypothesize that the cases most likely to miscarry are those in which the victim gets no more consideration from the legal system than a mentally disabled 8th grade drop-out like DeLuna; the cases in which many seemingly small discrepancies in the evidence are ignored until it’s much too late to correct the record.

Are we still to accept Scalia’s word that we don’t execute innocent people?

I don’t. But you don’t have to take me at my word either. Read The Wrong Carlos. Every factual claim we make is supported by a footnote in our digital companion that links to what we believe is the most complete set of primarily records in any U.S. capital case: crime-scene photos, law enforcement and court records, newspaper and TV coverage, and videotaped interviews.

Decide for yourselves.